We taught you the basics of bracket racing in a previous post. Now, we’re going to give you the next lesson—how to stage.

There is more to staging than simply rolling your car up to the starting line and taking off. There are staging techniques and tricks that will help you maximize elapsed times or reaction times—and once you master them, you can use them to win more races, more often.

The Guard Beam

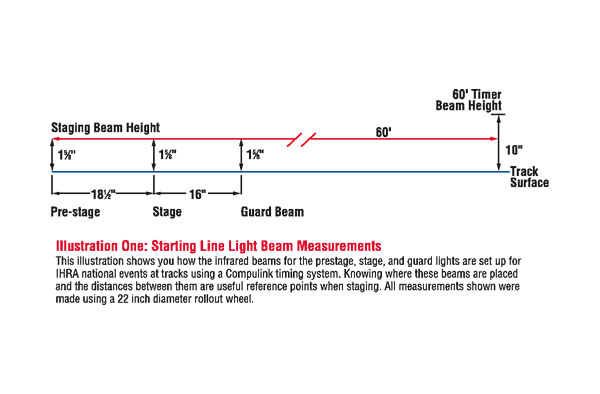

The starting line lights, or Christmas Tree, include two sets of staging lights—prestage and stage—that are linked to sensors that direct two infrared beams across each lane. When your car’s front tires interrupt the first beam, you trigger the prestage light. That lets you, your opponent, and the starting line official know you are close to the starting line. When you cross the second beam, you trigger the stage light, indicating you are ready to race.

Some tracks use a third infrared beam, called a guard beam. Its job is to prevent a part hanging underneath or in front of the car from blocking the stage and guard beams. This could result in giving a racer an unfair advantage by giving them a rolling start before the elapsed time (ET) clock starts and reducing the racer’s ET. A red foul light is triggered when the guard beam is activated while the stage light is still lit, automatically disqualifying the offending racer.

Rollout

A big factor in a good staging technique is rollout. Rollout is the distance it takes for the front tires to move past the stage beam and trigger the ET timer during the launch. Rollout has a direct impact on your reaction times. (Note: reaction time is measured by a different clock; it starts when the green light flashes and stops when the car completely unblocks the stage beam). More rollout increases reaction times, while less rollout decreases it. As a general rule, less rollout will improve your reaction times by allowing you to start the ET clock sooner.

Determining how much rollout to use depends largely on how you race. If you tend to go for the quickest elapsed times, then you want to minimize your rollout. If cutting a killer light is more your style, more rollout is what you need. You can also adjust your rollout to increase your chances of winning against an opponent. For example, if you and the racer you are matched up with run similar ETs, you can use more rollout and attempt to beat him based on reaction time.

Staging Techniques

That leads us to staging techniques. There are two basic types:

Shallow staging involves rolling through the starting area until both the prestage and stage lights are lit. This maximizes the amount of rollout you have, which improves elapsed time at the expense of reaction time. This is the technique recommended for new bracket racers until they learn proper launch procedures.

Deep staging is used to reduce reaction times. To deep stage, roll the car up until you trigger the prestage and stage lights, then move forward slowly until the prestage bulbs go out. This puts more of your front tires ahead of the stage beam—and less tire that needs to go through the stage beam and trigger the ET clock. That will improve your reaction time, but also increases your chances of redlighting if you don’t time your launch just right. Needless to say, deep staging requires plenty of practice; it may not even be allowed in some classes; check the rules at your track.

Like anything else, the best way to apply these staging and rollout techniques is to practice, practice, practice. Once you find a staging routine that works for you, stay with it. When you stage the same way for every run, the more consistent you will be—and consistency wins in bracket racing. Happy rollout hunting!

[…] consistency is more important than staging technique. No matter which technique you use—shallow or deep—success will only come after you have established a consistency and comfort level in the staging […]

[…] Originally Posted by Passmg2 View Post What does no roll out mean? Drag School: How to Stage Your Drag Car – OnAllCylinders WA 2 FST 2 is online now Quote Quick […]