There’s a lot of confusion about harmonic balancers.

There’s a lot of confusion about harmonic balancers.

Heck, we can’t even agree on the proper name. Is it a balancer or a damper (we tend to lump them all together)? And furthermore, what does it even do? In this post, we’ve enlisted the help of Summit Racing, Fluidampr, and ATI Performance to provide a basic understanding of harmonic balancers and learn how to choose the right one for a given engine and application.

To understand the function of a harmonic balancer, you need to first comprehend torsional vibration. According to Fluidampr, torsional vibration is the slight twisting and rebound of the crankshaft under torque during the power stroke. During each revolution of the crankshaft, the connecting rods and pistons are essentially slammed against the crankshaft as air and fuel are compressed within the cylinders. The crank actually flexes and unwinds, acting like a spring and creating torsional vibration.

Too much torsional vibration can lead to bearing wear, poor timing, power loss, and even total engine failure. In the worst case scenario, higher torque levels can cause the vibration to align with the rotating assembly’s natural resonate frequency. This phenomenon can cause the crankshaft to outright snap and lead to catastrophic engine failure.

Located on the crankshaft opposite from the end to which the flywheel is attached, the harmonic damper (or balancer) is charged with absorbing, or dampening, all this torsional vibration.

So is it a balancer or damper?

Although these names are used interchangeably, it is technically only a harmonic balancer when used in conjunction with an externally balanced crankshaft, which uses things like a harmonic damper/balancer or flywheel to balance the rotating assembly. (Internally balanced assemblies are able to rely solely on the crankshaft counterweights for balancing.) Whether the engine application is internally or externally balanced, the primary goal of the harmonic damper is to dampen torsional vibration or engine harmonics.

Based on design, there are several types of harmonic dampers. Most stock harmonic dampers are elastomer; however, there are three scenarios in which you would want to replace or upgrade from your stock damper:

- Worn or damaged stock damper: Over time, your stock rubber damper can wear or break down due to age or heat. The first signs of wear are generally cracked, bulging, or missing rubber.

- Added performance parts: If you’ve added performance parts, particularly ones that have increased torque, you’ve created more load on your crankshaft. This will produce added vibration that may go beyond what your stock elastomer damper can handle.

- Altered rotating assembly mass: Changes to the overall mass of the rotating assembly—lighter or heavier—can alter the resonate frequency or vibration characteristics of the crankshaft. Stock dampers are usually designed for a specific rpm range, and changes to the rotating assembly can mean the damper is no longer suited for the engine.

So which harmonic damper is right for your needs?

It typically comes down to design, diameter, and intended vehicle purpose.

Harmonic Damper Types

Different manufacturers use different designs for their dampers.

Elastomer

In this design, a rubber material connects the crankshaft hub and the inertia ring or weight, which controls much of the vibration. We mentioned this type of damper is used for stock applications, but some aftermarket manufacturers offer tuned elastomer designs which are specifically tuned to better handle high performance applications. ATI, for example, uses multiple rubber rings and different types of rubber to tune its dampers for specific applications. By using different ring diameters and materials, the company is able to create dampers tailored for specific rpm ranges where vibration is the worst.

These types of dampers tend to be cost-effective; however, detractors point to the limited movement of the bonded rubber before shearing.

Viscous or fluid

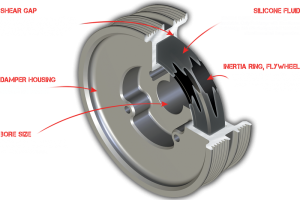

Viscous damper technology incorporates a thick fluid, often silicone, between an inertia ring and outer housing. As vibration causes the inertia ring and outer housing to spin back and forth and out of the phase with each other, a shearing action is created within the fluid in between. According to Fluidampr, which manufactures viscous dampers, this shearing action converts the vibration into heat and dissipates it through the outer housing.

These types of harmonic dampers can be pricier than their elastomer counterparts, but they often handle vibration through a broader rpm range. Because the fluid is not bonded to the damper like an elastomer design, it is unlimited in its ability to move and can be even more effective as rpms increase.

Friction-style

A third design uses a set of clutch discs to control vibration. By varying the style and size of the internal clutch discs, along with the spring-loaded pressure of these discs, manufacturers can effectively tune these dampers to an rpm range. And because the discs aren’t bonded to the damper, movement of the inertia rings are less limited than tuned elastomer-style setups.

Harmonic Damper Size

The overall diameter of the harmonic damper can affect its performance.

Choosing the right diameter comes down to a multitude of factors, including engine cubic inches, intended use of the vehicle, engine stroke, rpm range, and torque. All of these can affect the choice of diameter as well as harmonic damper mass. In addition, the use (or future use) of power adders can play a role in picking the right size since superchargers and nitrous shots can put additional forces on your crankshaft.

As a rule of thumb, the longer the stroke and greater the torque, the larger the diameter and mass. However, larger dampers can affect the acceleration and revving ability of an engine, so the right diameter and mass can help you strike the right balance. Manufacturers offer nodular iron, steel, and aluminum harmonic balancer options to help you dial in the right amount of mass for your application.

Be prepared to supply as much information as possible to your sales rep to zero in on the right choice.

Safety Ratings

If your harmonic damper will be used for competition, you may be required to use an SFI 18.1-approved damper. To meet this approval, a damper must be driven to a rotational speed between 12,500 and 13,500 rpm and maintained there for one hour. During this time, no part of the damper can become loose or separate.

Most race sanctioning bodies adhere to SFI standards so check your rulebook.

Installation Tips

Harmonic balancer installation tools and kits, like this one from Performance Tool, can make the job easier.

According to Fluidamper, it’s important to avoid common pitfalls when installing your damper:

- Use a proper balancer installation tool to avoid galling or damage to the crankshaft snout.

- Always apply a thin coat of anti-seize to ease installation and prevent galling.

- Verify proper fit with an accurate micrometer and bore gauge to meet the specified tolerances.

A harmonic damper isn’t glamorous, and it doesn’t make gobs of horsepower. But it is critical part of your engine’s performance, longevity, and overall wellbeing.

Choose wisely.

Hey Jeff, the brand name Rattles, can’t remember who produces, used to claim it was a true vibration remover. Not sure if still in production but was curious about your thoughts, as in gear drive cam vibration to the crank. Thanks, Larry

timing marks can become inaccurate

Even in this article the term “vibrations” has been used when the correct term should be “harmonics.” And the overall name of “harmonic balancer” is widely used when the correct term is “harmonic damper.” The basic purpose of a harmonic damper is to dampen the harmonics inherent in any engine. As mentioned in this article, a secondary purpose for a harmonic damper is on the minority of engines that require additional weight on the damper and the flex plate or flywheel to achieve proper engine balance. These engines, known as “externally balanced” engines do not have enough weight on the crankshaft counterweights to achieve proper engine balance. But the basic term for the device being discussed is “harmonic damper,” not “harmonic balancer.”

The basic term for YOU is “fool ” .Read the oxford dictionary automotive edition THERE it clearly explains a HAMONIC BALANCER BALANCES OUT THE HARMONICS

JIGGA, you are the “fool”, not Jim. Jim is correct. It is a harmonic damper. That is the correct engineering term. The “oxford dictionary automotive edition”, if it says what you claim, is also incorrect. It is clear that you don’t understand how a harmonic damper works, or what it does, if you did understand you would call it a harmonic damper. Instead, you descend to name calling. If you don’t understand, maybe learn or move on, don’t insult people who do understand.

Rattler.

Rattler

I have a problem with the puller. I got it at harbor freight and set it up I thought . I used the endpoint on the main screw. Should I have used the flat head end. I started cranking on the center screw and the bolts I used came out shaving some metal. Any suggestions? I have a 2001 Lexus GS 300. Thank you.