Is there a cheap way to increase compression on my small block Chevy? I have a 350 small block with iron heads. I don’t know much about the engine because it came in the car. The previous owner said it was rebuilt and has a cam but he couldn’t remember the specs. The other parts are an Edelbrock Performer intake, a 600 cfm Holley carb, and cast iron exhaust manifolds. The engine runs fine on the cheap 87-octane stuff and doesn’t ping at all. I’m thinking a little extra compression wouldn’t’ hurt but I can’t afford a set of aluminum heads. What do you think? Thanks

J.H.

Jeff Smith: Raising the compression ratio is an excellent idea for several reasons. Assuming that the added compression is not excessive, adding compression is the best way to improve power while also improving efficiency. There’s a reason that all the latest generation LS engines and especially the new gasoline direct injection (GDI) LT1 Corvette engine have higher compression ratios. The LT1 is designed to operate with premium fuel but comes from the factory with a true 11:1 static compression ratio.

Having said that, you can’t run that much compression on a small block Chevy using older, ‘70s vintage iron heads. We won’t get into all the details as to why but suffice to say that those older combustion chambers were not designed to accommodate that kind of compression. Internal combustion engineering has come a long way to achieve these higher static compression ratios and still operate on 91-93 octane fuel.

Since we don’t know much about your 350 small block, we’ll assume it employs the typical flat top, four eyebrow production pistons. With a composition head gasket, the piston 0.020-inch below deck, and a 76cc combustion chamber, and with a composition head gasket this puts the static compression at 8.5:1. This really isn’t bad. The standard Chevy 290-horsepower 350 Chevy crate engine you can buy isn’t even that good. Chevy’s literature states this is an 8:1 compression engine, and that’s what we found when we measured one of these engines a couple of years ago. This engine uses a dished piston with 13 cc’s of volume that reduces the compression.

One of the dimensions that is not easily changed is the distance from the piston top to the deck. In my compression ratio equation, I assumed the piston is 0.020-inch below the block deck surface, which is excessive, but we can use that to our advantage. If the pistons are closer to the deck (0.005-inch below for example), this improves the compression ratio but also limits the thickness of the head gasket since we are limited to roughly 0.040-inch for piston-to-head clearance. With a 0.020-inch negative deck height, this means we can use a thinner head gasket to improve the compression.

Of course, this means removing the cylinder heads to make this improvement and that’s where many guys don’t want to make the effort. Here’s how it works. We’ll assume that your engine is currently using a composition head gasket. These are quality head gaskets but are generally 0.041-inch thick. Adding the 0.020-inch deck height to the 0.041-inch head gasket creates a distance of 0.061-inch between the top of the piston and the flat portion of the cylinder head. This is called the quench area.

It’s interesting that many enthusiasts tend to overlook the combustion space as a place to improve engine power. The quench area is that flat portion of the piston that matches the flat portion of the combustion chamber on a wedge type cylinder head.

When the piston achieves top dead center (TDC), this creates a very tight clearance between the flat portion of the piston and the flat portion of the head. This area is called the quench space or sometimes called squish–which is a really good descriptor of its purpose. The quench area is designed to squeeze the trapped air and fuel in this area and squish it into the combustion chamber, creating turbulence. The key to quality combustion is to mix the air and fuel – or homogenize it. The quench area helps this process which tends to stabilize the speed of combustion once the spark plug lights.

The tighter you can get this quench area–or the piston-to-head clearance–the better the engine will run. Moving the piston closer to the deck surface also increases the static compression ratio. There is also a limit to piston-to-head clearance. Generally, for a low rpm street engine, you could be safe at 0.040-inch or slightly tighter. High rpm race engines with steel rods will fit into the same clearance but aluminum rod engines must use more clearance (perhaps around 0.050-inch) to accommodate the growth of the aluminum rods.

This photo shows checking the piston-to-deck clearance with a dial indicator. This is important information for blueprinting an engine and for accurately calculating the static compression ratio. It’s also critical for knowing the piston-to-head clearance.

Since it will not be feasible to disassemble your engine and deck the block, there’s an alternative idea. Fel-Pro makes a steel shim head gasket with a very thin rubber coating for a 4.00-inch bore 350 that is only 0.015-inch thick. When added to your 0.020-inch deck height, this produces a 0.035-inch piston-to-head clearance. This is a little tight but should be fine for a mild street engine that does not see engine speeds beyond 6,500 rpm.

The good news is that this gasket will bump the static compression ratio up to 8.97:1 or essentially 9:1, which is worth roughly a half a point in compression. A rule of thumb for engine is that a full point of compression is worth roughly 3 to 4 percent of engine power. Assuming 300 horsepower on your engine, a half-point of compression is probably worth almost 2 percent – which is only 6 horsepower. That sounds like a lot of work for a minimal improvement, but my guess is that low-speed torque will also improve at least this much if not perhaps a bit more.

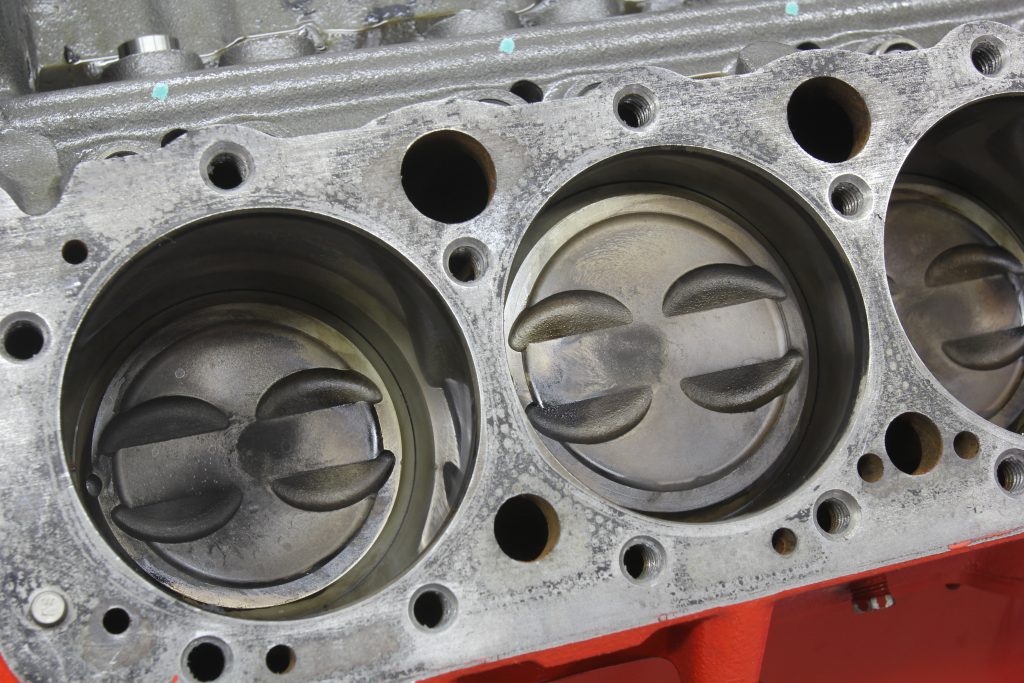

Here is a photo of a 290-horsepower small block with dished pistons. If your engine has these pistons, expect the compression to be around 8.0:1 which is at least 1.5 ratios away from where it needs to be. The easiest way to improve compression is with a set of 64cc chamber cylinder iron Vortec heads and that 0.015 head gasket, which will push the compression up to 9.0:1

One further recommendation would be to add a set of mid-length headers to the engine. This will do more to add power than any other thing you can do. Adding headers on a 290-horsepower small block was worth 30 ft.-lbs. of torque and 30 horsepower to that otherwise stock engine. My suggestion would be to do both the head gasket and the headers and then you will definitely need to re-jet the carburetor slightly richer unless it was excessively rich to begin with–which is also possible.

I was in a similar situation except that my engine is a small block 289 in a 1965 Mustang. The engine had been built, but other than observing the Edelbrock heads and manifold, headers, a Holley carb, and a lopey idle I had no idea what was inside. I was not happy with the soggy performance, however. When I performed a compression check, it came up evenly across the cylinders at 160 psi, which I thought was a little low. I suspected that the hydraulic cam in the engine may be partly to blame and as I wanted to hear the sound of solid lifters, I changed the cam. I used one of the custom cam grinders (Mike Jones) to help me select a cam. I wanted a shorter duration with the earlier closing of the intake – to help capture some of the compression. I also found that that the old cam was installed in a retarded position which added to the problem. In summary, the new cam made a world of difference throughout the rev range. It will buzz strong to 7,000 but still idle and pull in 5th gear (T5 Tremec) at 2,000 without problems. The tell tale of all this: the compression increased from 160 psi to 176 psi. with no other change. While the nominal compression ratio is important and often discussed, the cam timing will also impact the actual “dynamic” compression ratio and I think actual compression psi should always be checked as a guideline before and after any changes are made.

This link says that the LT1 had 11:1 compression ratio in 1970. Can this be done with the old heads? Or is this information incorrect on wiki.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chevrolet_LT-1

Old lt1 had big enough cam specs to bleed off enough cylinder pressure to make that 11:1 static compression work dynamically, the actual working compression.

That is correct. The compression is generated by a domed piston.

I have a chevy 350HO crate motor but want more lopey cam sound.

what can i do without head work.engine is in my 48 chevy pickup. i dont race it, just cruise to car shows

please advise

thanks dave

Want to raise compression on a 400 9.5.1 currently have 8-8.4 on 78 Ford 4×4

I have a 95 Honda accord with a 2.2L 4 cylinder engine and I’m getting no compression. The thing won’t even start. I’ve set the timing and replaced water pump cause it was over heating. But it stop running before I did all of that. Drove fine parked it and it wouldn’t start back up. Engine is engaging but won’t turn over.

lol, Leslie, what are you talking about? A bit out of context. Make sure the car isn’t in park 😛

That’s is some nice stuff to know. Thanks Jeff .

Can you buy aluminum heads that will bring the compression ratio up to 11:1 ? On a 350/333 hp crate engine? Thanks

I just recently built a 350 chevy. Im using 993 heads with z28 springs , its 060 over with .100 dome, a stage 2 rv cam 274 duration 430 intake 443 exhaust, 1.6 rockers , headers , qjet intake w 750 rochester…. I got it dynod. Results 355 hp 375 tq. Not bad..

I have a 283 bored 60over flat top pistons 461 stock heads 194-150 valves z25 cam can you tell me what my compression ratio is and how to raise it

Run 20/50 oil

hi

i have 1996 lt1 engine ,that im rebuilding now ,the heads ,as the technition said at machine shop that they are faced about 0.020, and we had to add another 0.010 for cleaning face for the heads. the mechanic said that we should go for adish pistons with 4 reliefs to keep the compression ratio ,within 10:1 compression ratio.

is that right calculation ?

the pistons are dish 4 reliefs and 0.030 over bore size .

im using also hotcam kit that include the camshaft, 1,6 rockers,valve spring.

so my question is how much compression ration this engine will have?

hi I have 350 sbc bored 30 over dish pistons heads are 64cc 180 intake 202 1.6 aluminum cam 213219 454 468 at112 head gasket 041 eldabrock performer cliffs qjet 2.5 ram horn exhaust 2.5 exhaust pipe it cam guessing 9-1 compression its in 3400 pd jeep 411 4 speed engine seems a little under powered what do you recommend different cam thiner head gadgets thanks for any input

Its compatible With moroso rear 2 piece seal adapter install a 1974 corvette L82 crankshaft,Pink rods and trw forged pistons 9:1 COMPRESSION RATIO IN A VORTEC 1999 5,7 TRUCK 880 ROLLER BLOCK,WHICH COMPRESION RATIO IS BEST WITH 62CC CHAMBER HEADS or 64CC Thank you

I have a stock 350cc engine in my 75 vette. I know “dog year” for horse power. Does the above tips work for my whopping 165 hp car?

Hey Raymond, before you go right into bumping the compression, Jeff’s got a pair of articles that talk in a broader sense about pulling power out of a 350 Chevy. They’ll give you a better idea of what you can do with your venerable 350. Check ’em out:

…

Ask Away! with Jeff Smith: Blueprint for a Budget Small Block Chevy Build

…

Ask Away! with Jeff Smith: Getting 400+ HP From an Old Small Block Chevy

I achieved .040” quench on a 307 with 283 heads. Custom pistons with 5cc valve reliefs gives me a very respectable 10:1 static compression ratio. Now I’m using 98 octane.

But be wary all, if you do away with the thicker head gasket for the .015” shim, you’ll very likely need to mill the faces of your intake manifold. Coolant leaks into a fresh motor is very annoying, could have been worse if I’d started it.

[…] the camshaft can increase the compression ratio, leading to a better-performing car […]

I have a 396 cu in with 325 hp, when cold it cranks and runs fine, but when it gets hot it seems the compression is so high it hardly turns over kindly like a weak battery, I have put a hi-torque starter on it and it still does the same. My question is should I put thicker head gaskets on it to reduce compression?

How much air pressure would it take to push a 10.1 piston?

I have a 2011 nissan navara and cylinder 2 has no compression and looking for a cheap way to fix it is there anyway I can get compression back so I don’t have to pay thousands of dollars just to get it fixed

So reading where you were saying you can run 175-185 psi cranking pressure. I planned the head on my lawn mower puller the pistons all already flush with the block Wisconsin THD engine when I get home I’ll check the cranking pressure again. Question is how do you know how much pressure the head gasket will take?

Hi Jeff,

I would like to know if it is normal for my 1.6 16 valve opel astra to do 19 bar per cylinder? We did the old compression test. My fiance did some work, changed the pistons and honned the block to accommodate. Not sure what else he did.

Thanks