More than 40 years ago, a friend came hobbling into my shop on crutches.

His right foot was in a cast. He wasn’t very happy. As the story goes, he was finishing up his Race Hemi-powered Belvedere and he ran out of bucks for a scattershield. Since he had all of the other parts ready, the car was temporarily assembled with a stock bellhousing. He figured everything would be peachy-keen with his clutchflite, especially for a single short clandestine test-and-tune ‘hit’ on the street.

But it wasn’t. Disaster struck.

Post-mortem, the consensus was the flywheel took a vacation. In turn, the clutch disc along with the clutchflite and most of the other clutch components were turned into lethal shrapnel and exited through the floor, through the dash and out through the windshield. Gerry’s pristine Belvedere two door post was a mess and his right foot was worse for wear (missing some pieces). Not good.

We’ve all heard similar stories. Some have experienced them. The solution of course, is a transmission shield (or scatter shield) or safety bellhousing of some sort.

There are several out there. Some of the best come from the folks at Quick Time. Their lineup is vast, but they all have one thing in common: the construction technique.

Quick Time bellhousings are spun, not formed.

The way it came about is interesting. Long time dirt track racer Ross McCombs worked for Musco Lighting at the time (Musco Lighting is the company supplying lighting for sports stadiums and other venues that require large, high-intensity lights). The company contracted to produce their huge light reflectors used a spinning process. McCombs noticed one of the workers was spinning cones for military ballistic missiles. Ross took note. As it turned out, McCombs had a problem with bellhousings for his racecar and he asked if they could spin him a bellhousing. The folks doing the spinning said no problem. Once the cone for the bellhousing was complete, Ross welded a plate to the back of the cone to mount the transmission, machined the appropriate holes in it and went racing. Pretty soon other folks took notice of the small, high quality bellhousing and they asked Ross if he could make a copy. It wasn’t long before McCombs was in the bellhousing biz.

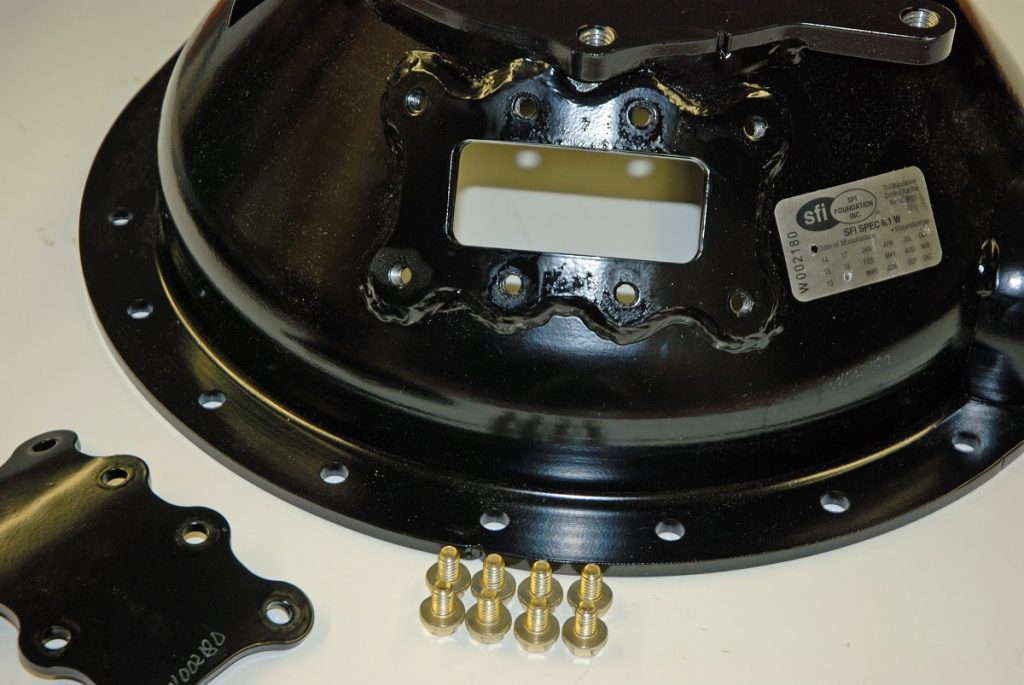

Over the years, Quick Time has evolved to produce what is likely the most accurate bellhousing in the biz. They hold 16 patents on the design and manufacturing process. Because of the spinning process, Quick Time is able to produce a dimensionally stable bellhousing with twice the strength of a conventional piece. Spinning the cone provides more strength because it work hardens the material (85,000 psi compared to 36,000 psi for other methods, according to McCombs). They’re so strong in fact they can withstand a catastrophic failure of a 29-pound flywheel spinning at over 10,000 rpm.

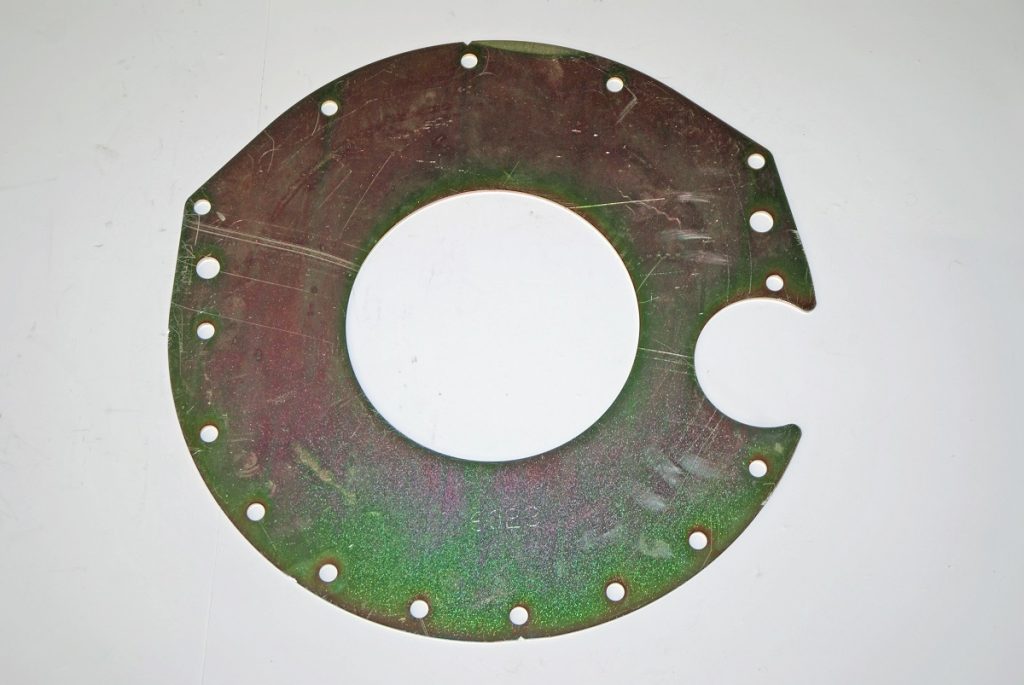

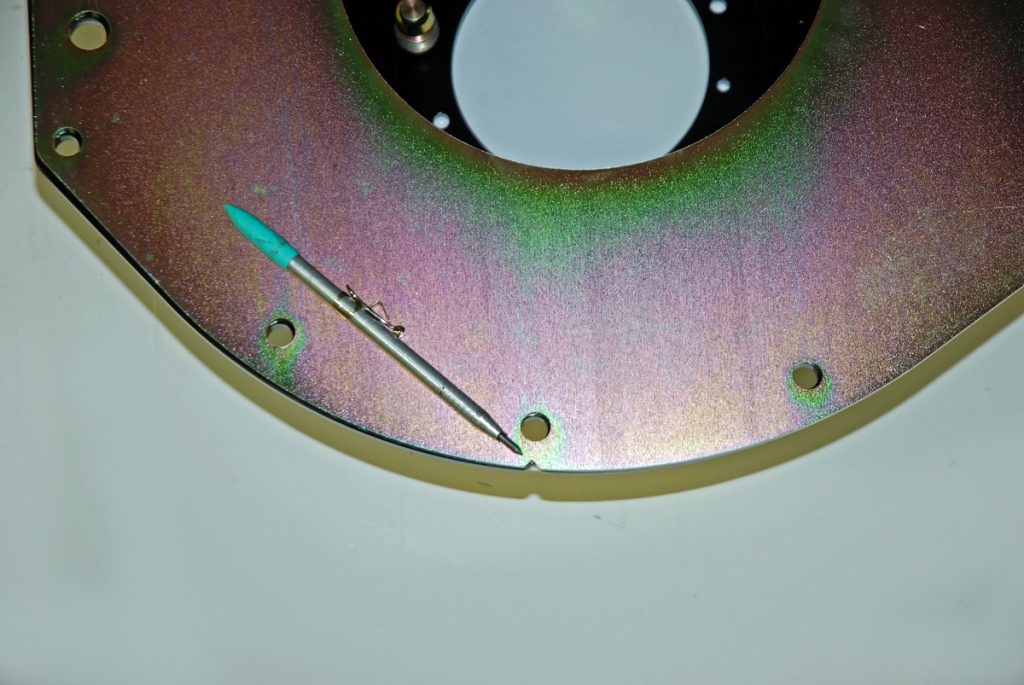

Something else the spinning process allows for is reduced size and heft. In some applications, a Quick Time bellhousing weighs half as much as a formed example. They’re dimensionally smaller too (smaller than some OEM aluminum bellhousings), particularly in the cone area. This allows for more header clearance, among other things. By the way, even with the reduced cone dimensions, it still fits big conventional clutch setups. We tested the bellhousing in the photos against a common 11-inch Hays diaphragm pressure plate and it all fits nicely.

In terms of construction, all of the openings in a Quick Time bellhousing are precision-cut using a five-axis laser and then the mounting holes are all drilled on a CNC machining center in one complete setup. This eliminates the chance of misalignment. The dowel pin and retainer bores are done last since they’re the most critical. These are machined to within a half thousandth of an inch of the OEM blueprint specification. Prior to shipment each bellhousing is 3D-scanned for accuracy and then powder-coated with polymer paint. Finally, these bellhousings are SFI certified and built in the USA.

Quick Time has more than 250 bellhousings available to fit 4,200 applications. They even offer bellhousings for non-original automatic applications (for example, a Ford small block equipped with a Powerglide).

The bottom line here is, these pieces are definitely designed to contain the carnage in the event of a clutch calamity. For a closer look, check out the accompanying photos:

True story. Mid ’60’s at Lions Dragstrip in Long Beach, CA. I and a friend were sitting in the stands when a (then) late model Mopar, a tech nightmare, hiked up and modified spit its clutch. Shrapnel and pieces of flywheel flew right at us and mostly over our head, except for a small fragment of the pressure plate that hit my friend in the head. The irresponsible racers, cowards as they were, just hustled off. The track did little to assist, despite the sight of blood. Emergency room for some stiches and a vow to never sit in that area again. Could have been worse. They were just lucky we did not have lawyers for parents.