Chevrolet’s LT1 engine family evokes all kinds of emotions among Bow-Tie guys.

Those in the know remember the original 350 cubic-inch LT1 introduced in 1970 was a real powerhouse with a hot mechanical cam and 370 horsepower on tap from the factory.

It was the last really hot Chevy small-block ever done, with the exception being the high-revving Trans Am-inspired 302 c.i.d. Z28 in 1969. The 350 LT1 rocked. In the years to follow, the LT1 lost adrenaline to tough federal emission standards and higher auto insurance rates. By the mid-1970s, the honeymoon was over.

As the 1980s unfolded, performance became more in style, with Chevrolet leading the pack in that age-old battle with Ford. Those fuel-injected 5.0L Mustangs were a force to be reckoned with and Chevrolet was paying close attention. Chevrolet brought us Cross-Fire injection in 1982, which didn’t impress anyone. In the mid-1980s, GM brought us Tuned Port Injection (TPI), which was tunable and certainly a smashing success. TPI endured and remained an industry standard for years.

The redesigned Gen. II LT1 Chevrolet small-block (L98) introduced in the 1992 Corvette was an updated version of the time-proven small-block first introduced in 1955 with its share of interesting refinements—some quite controversial.

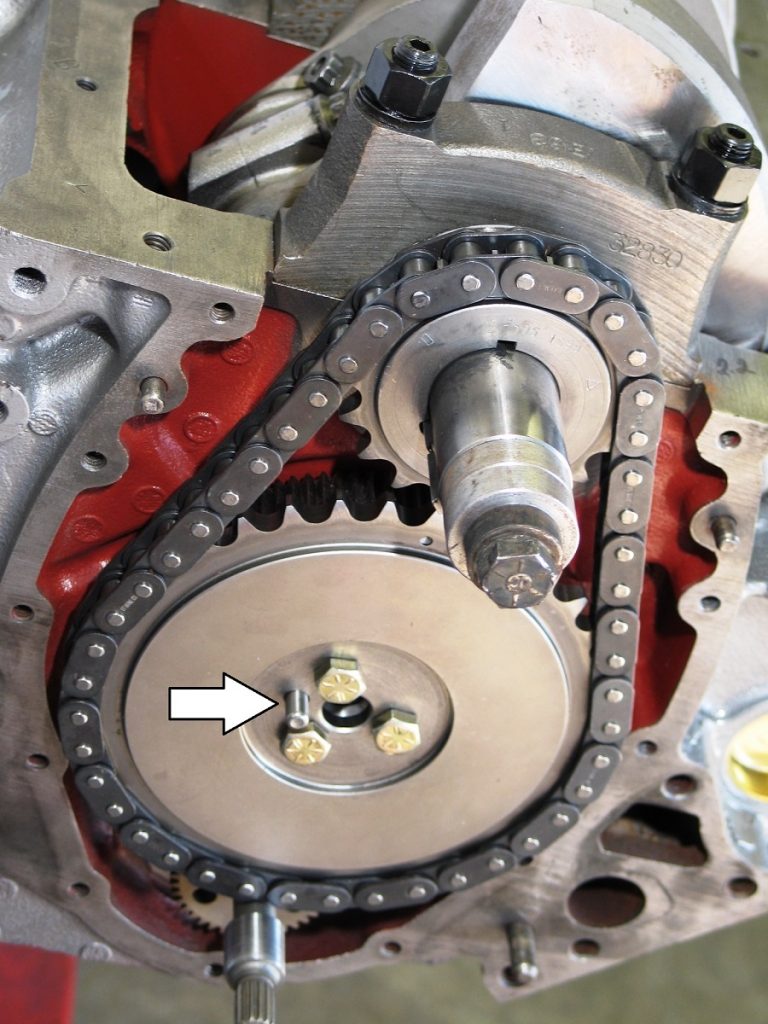

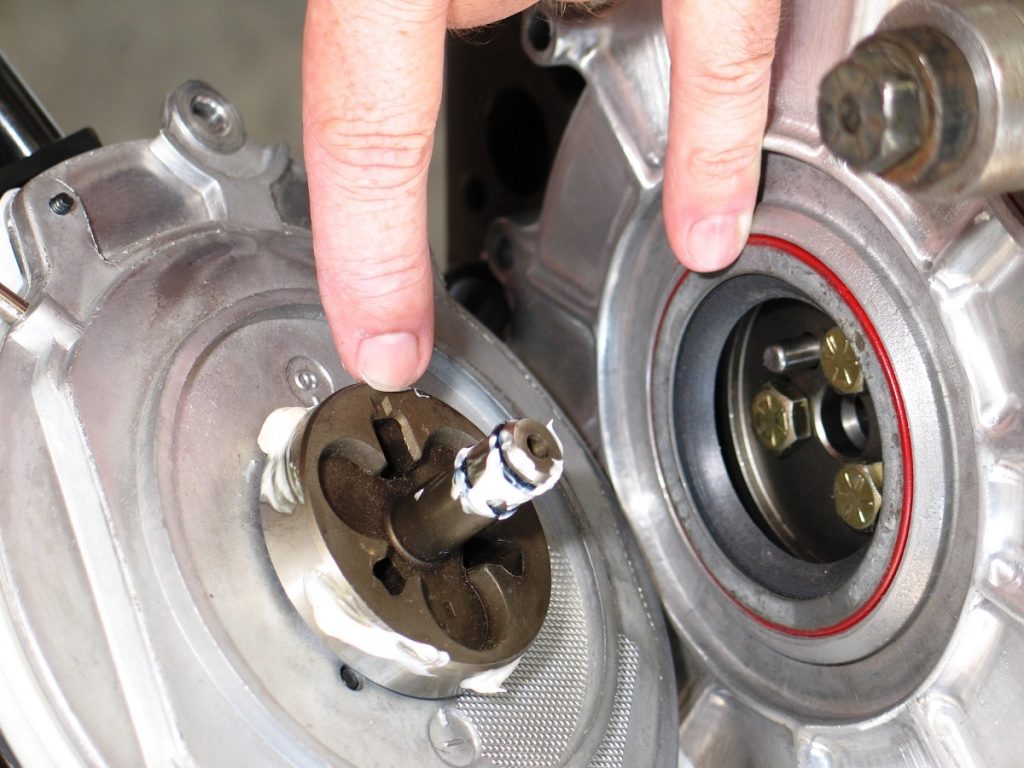

The cam-driven water pump with reverse-flow cooling and OptiSpark ignition system were revolutionary. However, OptiSpark has always been problematic. It has also been refined and improved by both GM and the aftermarket. MSD, as one example, offers a terrific OptiSpark replacement distributor as does Accel.

You can even retrofit the LT1/LT4 with a cool LS coil-on-plug ignition system and eliminate OptiSpark entirely.

The Lingenfelter Performance Engineering coil-on-plug conversion solves the OptiSpark ignition issues. The LT1 coil-on-plug converters with adjustable retard and intelligent rev limiter still use the optical module in the OptiSpark distributor, but without high-voltage passing through it.

Inside the LTCC package, you have the LTCC module and the harness with eight leads, each with a Weatherpack connector and ground wire, a pigtail connector, and four non-harnessed wires. There are plenty of OptiSpark ignition choices to meet your ignition needs.

The LT1 engine in displacements of 265 and 350 cubic inches was employed in a number of General Motors vehicles including the 1992-’96 Corvette, 1993-’97 Camaro and Firebird, 1994-’96 Chevy Caprice and Impala, Buick Roadmaster, and the beasty Cadillac Fleetwood luxury rides.

What made the LT1 series so successful was greater amounts of power by yielding a broader torque curve enabling full-sized luxury cars to accelerate aggressively to speed onto the freeway. In performance vehicles like the Impala SS, Camaro, and Firebird, it roared out of traffic lights in an inspiring fashion. It rocked. What’s more, there was so much you could do with it in terms of performance.

Let’s Get to It

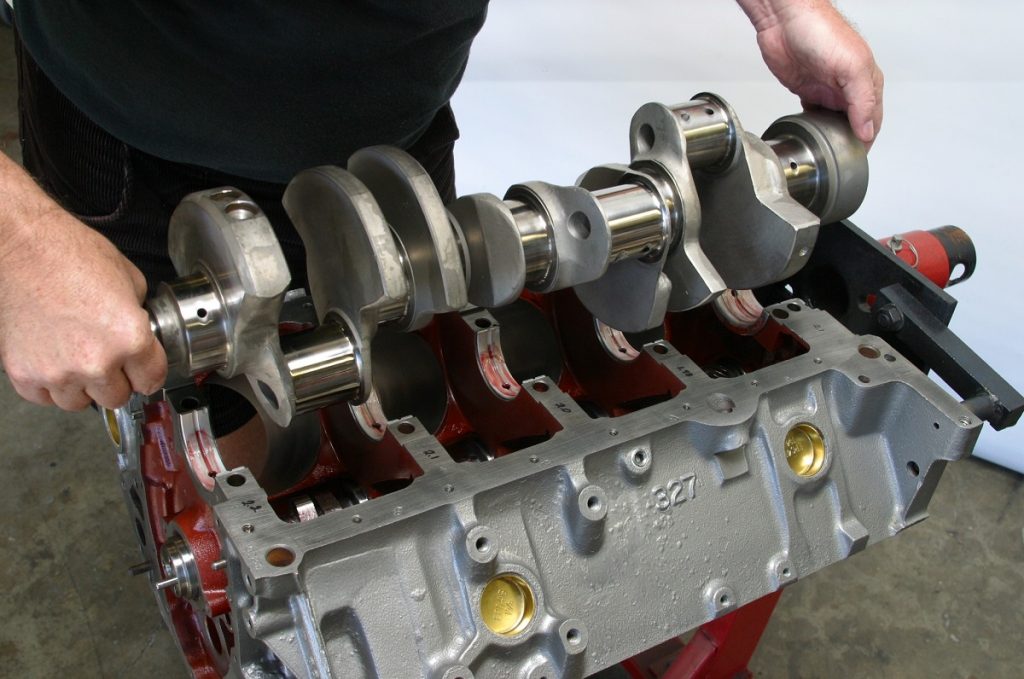

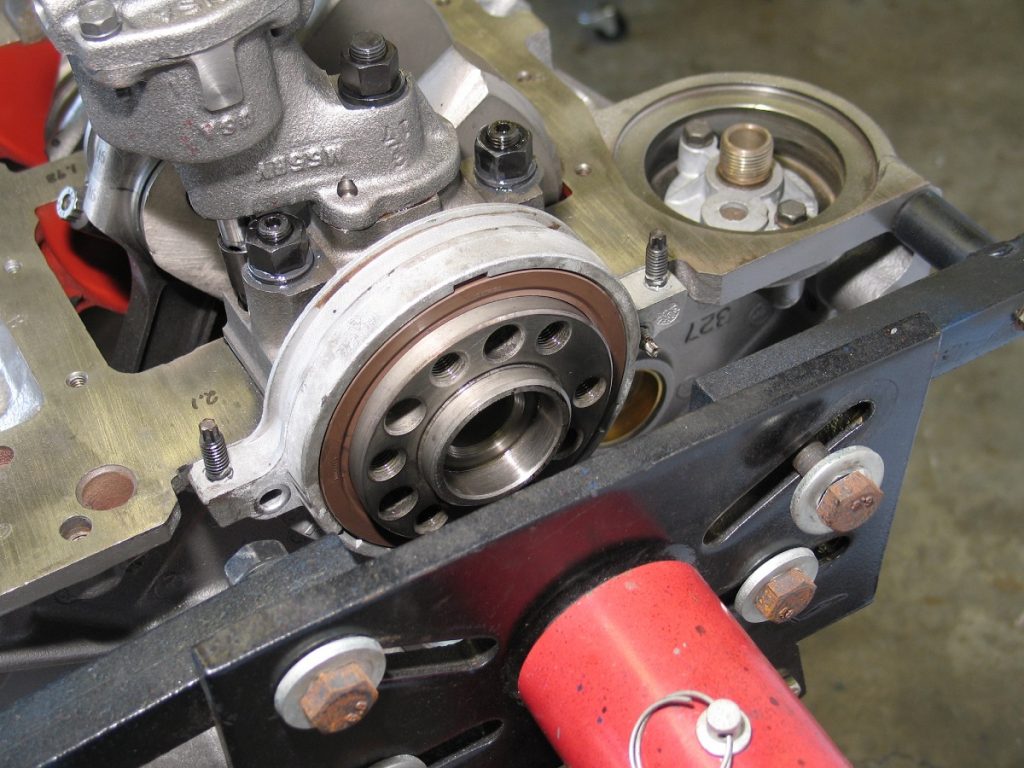

We’re working with a 1996 vintage LT1 block, identifiable by its “327” visible in the block and a casting number of #10125327 for the 5.7L V8 with a 4.000-inch bore.

This block casting was used from 1992-97. There’s only one other LT1 block casting numbered #10168588 for the smaller bore (3.736-inches) L99 4.3L V8 (265 c.i.d.), which was available in the Caprice as the base V8. What we’re about to do here applies to both the 350 and the 265.

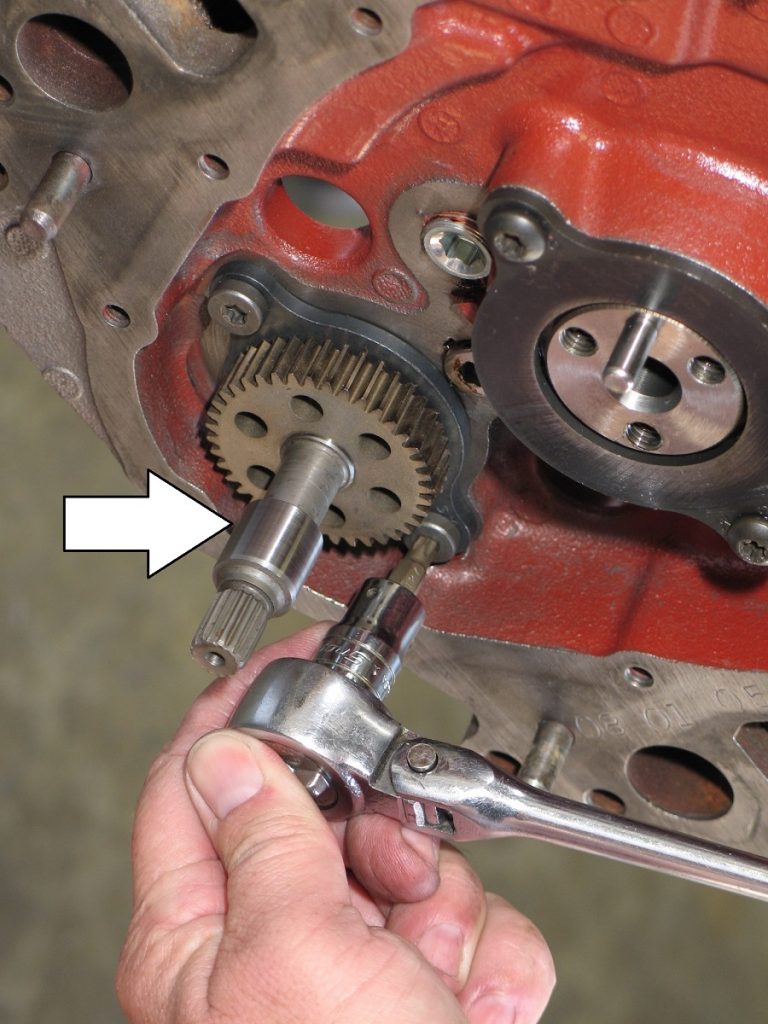

What makes the 1992-97 LT1 block different from the traditional Chevy small-block is what it has—and what it doesn’t have. It doesn’t have an accommodation for a distributor like most Chevy small blocks. Instead, it has an oil pump drive stuffed in the block in back secured by a single bolt. The LT1 block really is an entirely different block and needs to be treated as such. Some items are interchangeable—some are not. Intake manifolds, as one example, are not.

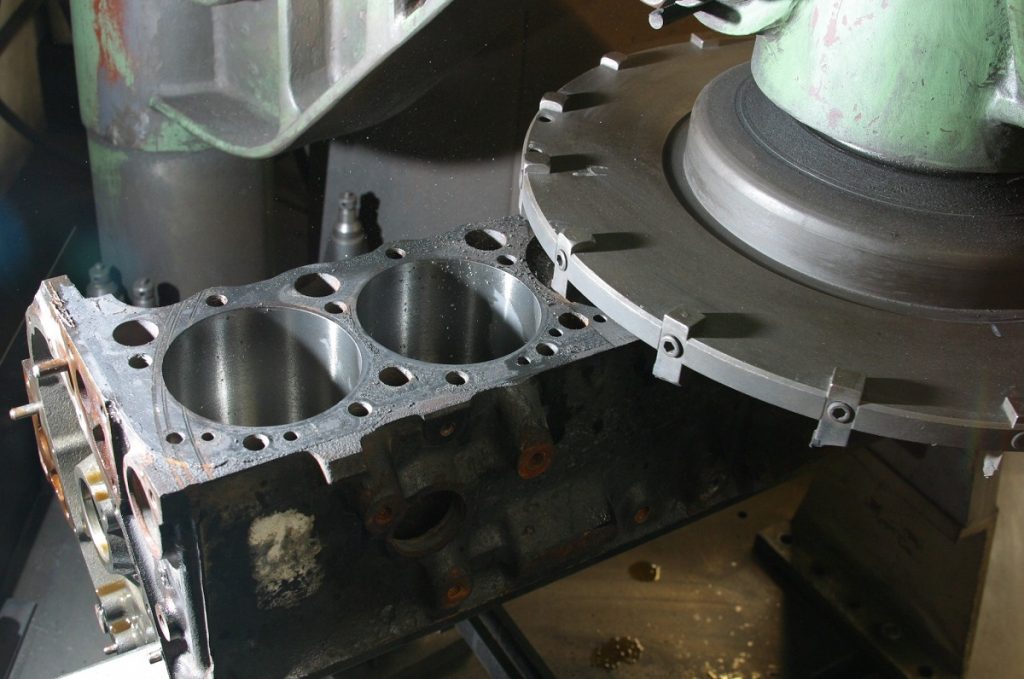

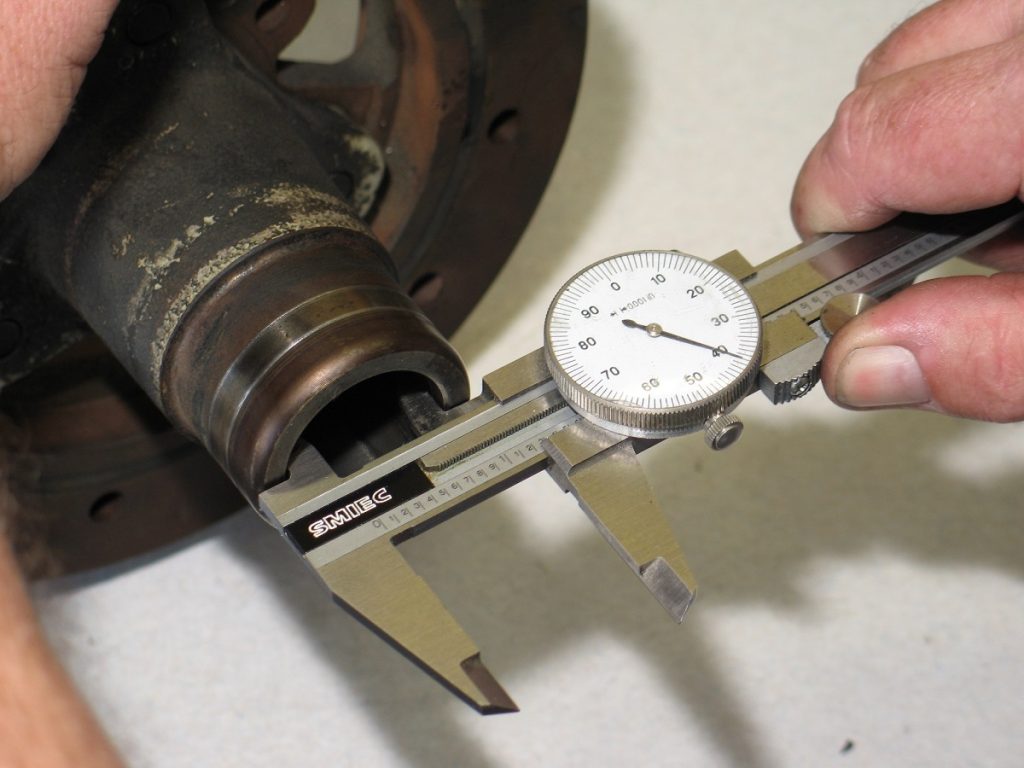

L&R Engines of Los Angeles, CA provided us with a standard bore LT1 5.7L block bored and honed .030-inch oversize (4.030”). The block has been professionally cleaned, prepped and machined for this build effort. This block has been line-honed, bored and honed, and the decks cut to give us a clean, crisp, ready to assemble short-block.

When Chevrolet introduced the 300-hp LT1 (Gen. II) fuel-injected small-block in 1992, it was a more-advanced 350 c.i.d. Chevrolet V-8 small-block, which was a cut above the Tuned Port Injection small-block first introduced in 1984.

TPI set a new benchmark for performance when it debuted in the all-new 1984 Corvette and the white-hot 1985 IROC-Z Camaro. It offered incredible performance coupled with something unheard of with high-performance V8 engines of the era—fuel economy. Port fuel injection coupled with aggressive roller tappet technology made the TPI a quantum leap in performance. No one did it better than Chevrolet.

The new Chevy Gen. II LT1 took TPI to the next level with features that made it a vastly improved small block. The objective was reduced emissions and greater amounts of power. GM did away with the belt-driven water pump and rear HEI distributor—replaced with a camshaft-driven, reverse-flow water pump, and OptiSpark ignition.

OptiSpark was a pancake-style, light-triggered electronic distributor located beneath the cam-driven water pump. There were two types of OptiSpark ignition systems. There was the unvented (1992-’94) and vented (1995-’97). You will want the vented OptiSpark.

A reverse-flow cooling system was conceived to compensate for the much higher 10.5:1 compression ratio long with leaner fuel mixtures to clean up emissions. Reverse-flow became the standard all across the auto industry.

Chevrolet’s selling point in technology would also be the Gen. II’s undoing. OptiSpark was plagued with reliability problems that troubled Corvettes, Camaros, and other GM models in the 1990s. Oil leaks around the water pump drive not only spotted driveways, but Chevrolet’s great reputation for reliability and performance. Between GM’s efforts, and the aftermarket’s, these problems aren’t as bad as they used to be. However, they have to be a priority for your LT1 build. Your job is to build a trouble-free LT1/LT4.

Despite the LT1’s engineering shortcomings up front, it was a terrific factory small block sporting a nodular iron crank, powdered metal “cracked” connecting rods, and hypereutectic pistons. In 1992, the LT1 yielded 300 hp. By the end of production in 1997, it was making 330 factory ponies in the powerful LT4.

GM made two types of Gen II LT1 blocks in the 1990s—two-bolt main and four-bolt main. Four-bolt main versions were factory installed in Corvettes mostly. However—expect to see the four-bolt main LT block in nearly anything built in the 1990s. Because they both have the same casting number of “327” they are impossible to confirm without removing the oil pan.

Although most 1992-97 LT1 engines had aluminum heads, it is important to remember there are LT1s with iron heads found in full-size GM sedans of the era. The Caprices had similar-looking 265 c.i.d. small-blocks (L99) that resemble the LT1. These engines are easily identified by their smaller 3.740-inch bores and iron heads. Don’t accidentally pick one of these up for your LT1 build project.

When we decided to build a Gen. II LT1 383 stroker, we understood it was a significant turning point in the small-block Chevy’s 37-year history. It would also be the small-block Chevrolet’s curtain call—the end of a very successful design run that would end on a mass scale at the 42-year mark.

Truth is, Chevrolet never really stopped building small blocks because they’re still available as crate engines from Chevrolet Performance. And if you’re really into numbers, Chevy has built well in excess of 90 million small blocks since 1955. It is easily the most common V8 engine ever produced and distributed around the world.

We’re building a solid, reliable LT1 383 c.i.d. stroker to see just how much power we can make from GM’s LT1 5.7L engine.

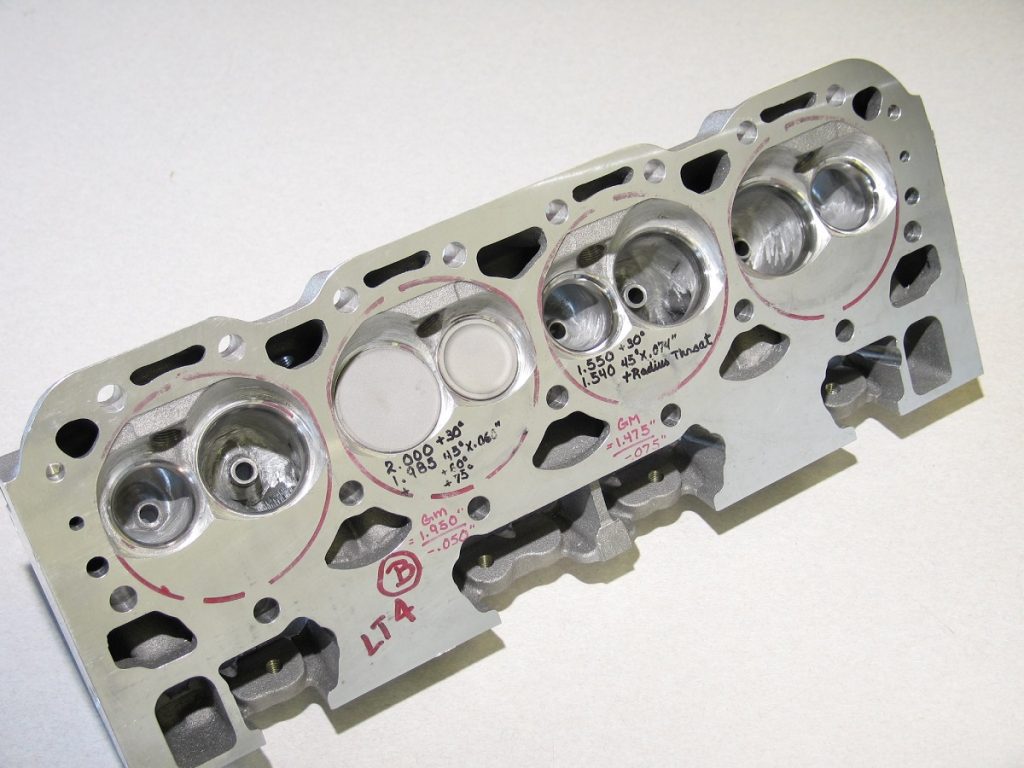

Mark Jeffrey of Trans Am Racing in Gardena, CA volunteered to build our LT1 turned LT4, with the objective being 450 hp, with a broad, stump-pulling torque curve. Mark had Air Flow Research cylinder heads in mind for our LT1 build along with an aggressive street cam package that would be good for both the commute and racetrack.

However, the car’s owner wanted a stealthy—stock in appearance, using as many genuine GM parts as we could muster on the surface. We copped LT4 heads and induction from Chevrolet Performance, which were available at the time this engine was built in 2005. Thanks to a 383 c.i.d. stroker kit from Coast High Performance, a hot roller cam kit from COMP Cams, and custom port and bowl work from Mark Jeffrey at Trans Am Racing, we were able to take a 300-horse LT1 and make 475 hp. Imagine what you could do with AFR heads— which would push it way over 500 horsepower.

Let’s get started.

LT1/LT4 Cylinder Head Types

GM produced a number of LT1 cylinder heads during the 1990s. Here’s how they stack up. Be careful when shopping for these heads—there were eight different aluminum cylinder head castings produced for the LT1/LT4. LT1/LT4 heads employ rail-style self-aligning rocker arms similar to the LS.

What’s more, the valve covers employ bolts through the center of the cover unlike perimeter style bolts on the small block Chevy and even early LS engines. Keep squarely in mind LT1 heads and intake do not interchange with LT4. If you have LT4 heads, you must use the LT4 intake. What makes the LT4 head and induction better is improved port flow and greater compression.

LT1/LT4 Aluminum Head Identification

| Type | Specifics | Model Year | Displacement | GM Casting Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LT1 | Intake 175cc Exhaust 68cc Chamber Size 53cc | 1992-97 | 350/5.7L | 10128374 |

| LT1 | Intake 175cc Exhaust 68cc Chamber Size 53cc | 1992-97 | 350/5.7L | 10205245 |

| LT1 | Intake 175cc Exhaust 68cc Chamber Size 53cc | 1994-96 | 350/5.7L | 10207643 |

| LT1 | Intake 175cc Exhaust 68cc Chamber Size 53cc | 1996 | 350/5.7L | 12551561 |

| LT4 | Intake 195cc Exhaust 68cc Chamber Size 52cc | 1996-97 | 350/5.7L | 10239902 |

| LT4 | Intake 195cc Exhaust 68cc Chamber Size 52cc | 1992-97 | 350/5.7L | 12555690 |

[…] Chevrolet’s LT1 engine family evokes all kinds of emotions among Bow-Tie guys. Those in the know remember the original 350 cubic-inch LT1 introduced in 1970 was a real powerhouse with […] Read full article at http://www.onallcylinders.com […]

I bought a lot of older trucks that have the LT1 block but a football main I find them a lot and then mostly in a 95 to 96 trucks the 1500s and the suburbans I hear these blocks or with anywhere from 1,000 to 1500 is that true for the one that have the four bolt main I know they’re getting scarce and harder to find by looking at the front of the block and looking at the heads what’s the difference between an LT1 and an lt4 block it was interesting reviewing this on Thanksgiving morning I should be fishing but instead I’m looking up old engines worrying about past times I don’t know I hope you have a good Thanksgiving thank you big Doug K.: I recently rebuilt one of the new 440 hemi 5.7 which is a slanted motor I guess you have to have precision putting the Pistons and everything back in line otherwise the motor won’t turn over because it’s all on an angle my rotor runs really strong it was really good it felt good to do something new I see that a lot of people don’t like to mess with this motor because of its complications and expects why are people afraid of things that we have overcome 20 years in racing and 40 years in racing if x equal y and why equals 20 then we should know the equation and have the answer it’s not that hard is it or people believe it’s hard just like electronics nowadays I find that people don’t understand that the PCM is the boss of the Enterprise and all the other components are offices they have to be open and find out who is at work and who’s not at work for the engine to run and for the car to do what the computer supposed to do with it if people take that understanding it makes it easier this was something that was taught to me 4 years ago but you have to remember when somebody doesn’t show up for work and you replace him you got to let the boss know that they’ve been replaced people forget to do this and seem to complicate things with the PCM the big boss have you found this problem with people too and the new computer systems I found that Dodge seem to complicated things by making you have to go through the system and delete the DC could and the TDC codes and a certain pattern if you don’t do it in the right pattern they all show back up and confuse the PCM have you run into this problem with other cars or just a Dodge

Gen2 LT1 blocks were never installed in trucks from the factory. Only in Corvettes, F bodies, and B bodies.

Information overload but what I always wanted to know these facts. The stupid question I was always afraid to ask my shop teacher:) I love and feed off of this. I will attempt to memorize this article within the next 2 years:(

Thanks

Holmes if you call this information overload, maybe you should go back to some old issues of many of the now defunct car magazines.

This was well written and informative. Period

I’ve a ‘96 lt4 Corvette that I am collecting parts for a 383 build. If I am aiming for 450-500 hp, will the 4blt. main main block be a good starting point for the build? I keep hearing that the 4blt main block may be prone to cracks along the main web area. Should I start with a 2blt block and machine splayed 4blt mains?

2 bolt blocks are fine at that horsepower level..

Not to mention splayed blocks unfilled are actually weaker in a production block setup as opposed to a bow tie or dart block mho..

It’s a lie that 4 bolt mains are weaker than 2 bolt mains. The order of strength for SBCs is splayed billet 4 bolt main caps, straight 4 bolt main caps then 2 bolt main caps. All three setups are stronger with studs than bolts.

hi guys,, i wanna know if sbc gen 1 engine oil restrictors..will fit Lt1 engine.. i cant find part number for lt1 engine oil restrictors.. thanks…

Will the Gen II Lt1 heads work on my 87 359 block

In the article above you mentioned how the stock harmonic dampner had to be machined to fit, but also mentioned that a new one could be purchased from Summit. Do you have the Summit part number? I purchased a new Eagle stroker crank and I purchased a new harmonic dampner hub. It does not fit the new crank. I called Summit and they could not help. They referred me to call Eagle. I can try to find a machine shop to open the ID of the new hub if Eagle has no response. Rebuilding this LT4 has been a challenge. The previous stroker crank broke at the first rod journal. Thanks for help.

[…] The most obvious answer to adding torque was with displacement, and GM did exactly that by offering a larger, more powerful 5.7L version of the LT1. […]

I have a 97 tranam I was trying to see how can I get about 500hp out the lt1

I have a 96 LT1, I saw a video where a guy machined his block to accommodate a carberator and intake, I was wondering why no one on here mentioned it, is not possible, could it be done????

Hey Sylvester, Sure you can convert an 1990s-era LT1 to carb. For starters, there are intake manifolds available that allow you to run a carburetor on an LT1 block. Check out this one from Chevrolet Performance, as an example. You’ll probably need to ditch the Optispark and go with a more traditional distributor-based ignition setup though. If you’d like some specific help on the conversion, contact the Summit Racing tech folks.

I need help with my 96 lt1 it something dealing with the air and gas

I just bought an Lt1 5.7 engine minus crank and cam and pistons. I want to bring this in at around 400 h.p. From what I can tell it’s been bored .30 over it all looked really clean and fairly newly redone. I did find a bent push rod with the side ground down in a check mark type shape, but the person I bought this from doesn’t know the history he received it in a trade. All # on heads and intake match your guides and the fuel rail is set up on passenger side. Is this corvette. All the help you can give me would be greatly appreciated. This will be my first build at 59 yrs old.

Hey Terry, I found this forum thread over at CamaroZ28.com that may be able to help ID your engine.

[…] power based on that fuel flow. Our research indicates that the stock injectors for the 1990s-era Chevy LT1 engine were 24 pounds per hour (lbs./hr.). This number by itself isn’t really that enlightening. But we […]

Greetings to all.

It would have helped a lot to those of us who have LT1 / LT4 and want more power, to have left the list and number of parts.

If someone has them, it would be very good for everyone.

Thanks!

Do you have a optispark delete kit for a 1992 Corvette LT1 engine and if you do could you send me the price and what is included in the kit.

Hello , 10125327 block vett engen I’m installing it in a 88chev k-5 blazer wiring , to stock how and who does these wiring kits . Witch one works best . Thank you

88 chev k-5 conv to 97 corvette 10125327 wire harness who builds the best harness?

The 1997 Corvette was the first GM car to get the soon-to-be legendary LS engine, a 5.7L LS1 to be exact. So are you asking about a standalone engine management system for an LS swap? Good news, you have plenty of options–click here to check ’em out.

…

Summit Racing also has an entire page dedicated to LS Swaps. And there’s a sub-page for 1973-91 GM C-series trucks, which are pretty closely related to your K5 Blazer. You might was to check that out too.

I have a 1969 350 bored .030 over I got it that way. The stamped number is 19S731239 V0924HZ. casting number is 20GM-3917010. Is it possible to upgrade to a LT4 induction fuel rail system?

Thanks

Ron Warrens

No.

The best you can do is upgrade to a Vortec heads & intake / ECU system. Mid 90’s trucks and vans are your source. Conventional SBC block with standard flow but the port & combustion chambers are considered copies of the LT1 design.

Better to go with a whole L31 engine since you also get 1 piece rear main seal and upgraded oil pan gasket for 99% less leaks as well as built in roller cam.

I have a 1995 Z28 with the factory 5.7 LT1 engine and 4L60e tranny. Since both time and money is scarce I purchase a low milage VO127SAS V8 Lt engine from a Buick Road master. The engine came without heads orintake manifold but appears to be in great shape. Can you tell me if this RM Lt1 will accept parts from the “95” Camaro LT1?

The only block castings for 92′ – 97 LT-1 are 10125327 for the 5.7L V8 with a 4.000-inch bore and 10168588 for the smaller bore (3.736-inches) L99 4.3L V8 (265 c.i.d.). Heads will bolt on both although you may have interference between the valves and block and will have air flow shrouding issues with the smaller block.

Anything else will require some type of machine work and is not a ‘bolt together’ application.

Where did you get this VO127SAS? GM never uses letters in their part numbering system.

If I’m putting together a grocery getter out of a 92 suburban it’s a 5.7 cast iron heads is it the same reverse flow or is the standard is a gen 1 also putting a Edelbrock intake carburetor and HEI distributor they say stay away from those engines why is that once again it’s daily transpo

I have a 1996 LT1 from a Trans Am that I am putting in a 1969 Camaro. The motor I bought is pretty bare for externally attached components. I will use a Painless Performance harness that will explain the electrical for me, but what I need to know is all the other components routing and attachments. Does this book go to that detail? Basically an external component assembly manual. How to hook up stuff and to what…

I own a 1996 Corvette with a 5.7L, LT1. Can you help me find new water pump mount bolts( 9440073-9423592) and belt tensioner mount bolt( 10105370)?

did they change 96 lt4 enough to accept LS components like intake?

Hi,

I have a gen 2 engine that I’m switching to Chevy Intake and Sniper EFI, my question is in regards to the cam shaft and the removal of the Optispark. I read that the cover can be welded up when removing the stock ignition, but will there be an issue with the cam shaft end play and the lack of an accessory taking up the slack? I’ve also heard about a stock bracket that keeps the cam from moving forward but the details are somewhat vague.

Thanks,

Jim from Scottsdale

Can I safely bolt a set of LT4 (Intake 195cc Exhaust 68cc Chamber Size 52cc 1992-97 350/5.7L 12555690) heads and LT4 intake to my 1996 base LT1 corvette?

I have a ’96 Roadmaster Estate Collectors Edition 4D 8-5.7L Gasoline SF1. I luv the big old tank, but only drove it every month or two and EVIL squirrels and mice stuffed 5-6 dozen walnuts, grass and nesting in the engine compartment. I cleaned the crap out and did a monthly drive (TWICE). The last one got me 4 miles away and it died.

Towed to mechanic who said it ran for 3 hours sitting in their lot. When inspected found most wires and vacuum hoses eaten into, couldn’t get valid readings from the computer and the heater blower was full of grass and the housing eaten also.

Long story (DUH) short? Is the engine worth trying to sell or just junk it all?

Thanks VERY much, John Schmidt

Hey John, realize you’re talking to an extremely biased crowd here, but–a V8 powered full size wagon is almost always worth saving in our book! Did the engine run OK before all this happened? Any smoke, knocks, or pings? How many miles were on it?

…

At its heart, the SBC architecture is about as reliable as you can get (yes, even with the Optispark), so if the engine seemed fine before all this happened, then I’d start the tedious project of repairing wires and replacing those vacuum lines. Heck, you could even go as far as standalone engine management–but you may find that a few fixed wires, some new vacuum lines, and a good cleaning will get the old wagon back up to snuff.

…

Good luck! We loved those 1990s-era GM Full Size Wagons!

Bore: 4.030. Stroke: 3.75. Deck clearance: 0. Head Gasket: .040.

With 53cc head chambers, you’ll need to find 21cc dished pistons for 10.5:1 CR. I have not seen these anywhere.

Speed pro has tons of them. Summit Jegs, Ebay even autozone can order them. Tons available.

Yeah, sorry for the late replay here, but Summit Racing has plenty of options in the 4.030/3.750 bore/.stroke spec. Check out hundreds of pistons here at SummitRacing.com and you can find several with the with the 21cc dish too.