Some folks tend to use the terms ladder bars and traction bars interchangeably. Both are traction aids, but there are some big differences in how they work and which will ones are better for your car.

What Are Ladder Bars?

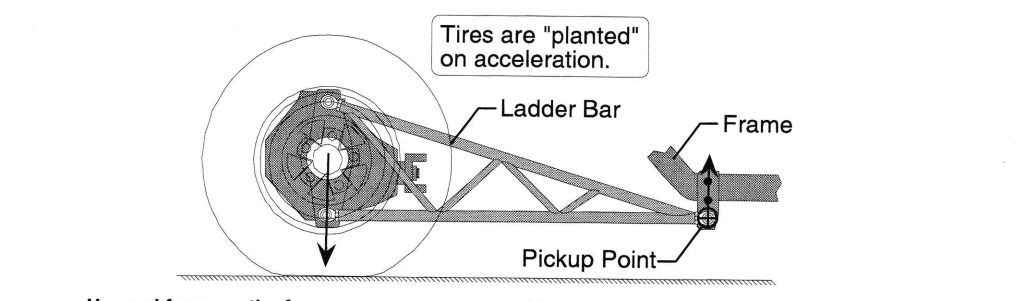

Prior to four link suspension systems coming into vogue, the ladder bar was the go-to setup many racers used to control rear axle housing wrapup. A ladder bar is simply a triangular shaped member that connects the rear axle housing to the frame, usually by welding.

According to Jerry Bickel Race Cars:

“The ladder bar prevents excessive wrapup by pushing up on the frame at the point of connection. The front of the car is lifted or “picked up” by this action, so the attachment point is called the pickup point. Since the car typically has two ladder bars (on each side of the rear end housing), there are two pickup points. As the ladder bars push up on the chassis at the pickup point, they push down on the wheels and tires. This plants the tires forcefully, creating better traction.”

“Racers soon discovered that pickup point locations have a lot to do with the behavior of the chassis. Short, high pickup point locations create a violent action in the chassis that may wad the drag slicks excessively at launch. Afterwards, there may not be enough load transfer to keep the tires planted. Both issues reduce tire traction and increase elapsed times. Short, high pickup points also cause severe body separation at launch, resulting in poor driveshaft alignment.”

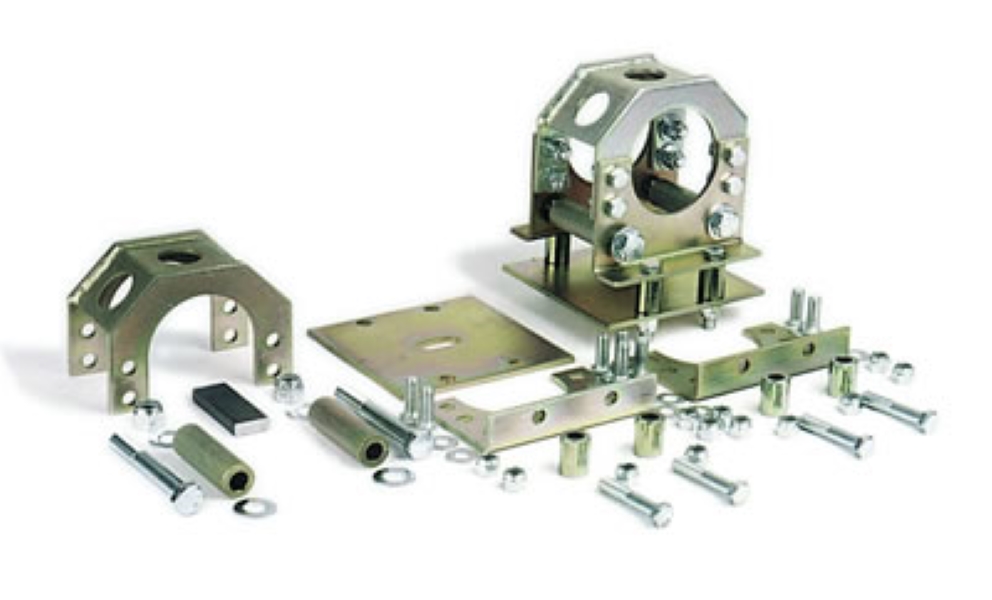

A good ladder bar setup is designed to be welded to the car. Some early ladder bars bolted on, such as the ones made for vintage GM four-link suspensions. Were they effective? Probably not.

Ladder bars can be used on cars with leaf springs or coils. If ladder bars are used with leaf springs, the car will immediately encounter bind. That’s why leaf spring cars with weld-on traction devices must use some form of axle housing floater. if the suspension system has a coil spring of some sort (most often, a coil-over shock), bind is not an issue.

What Are Traction Bars?

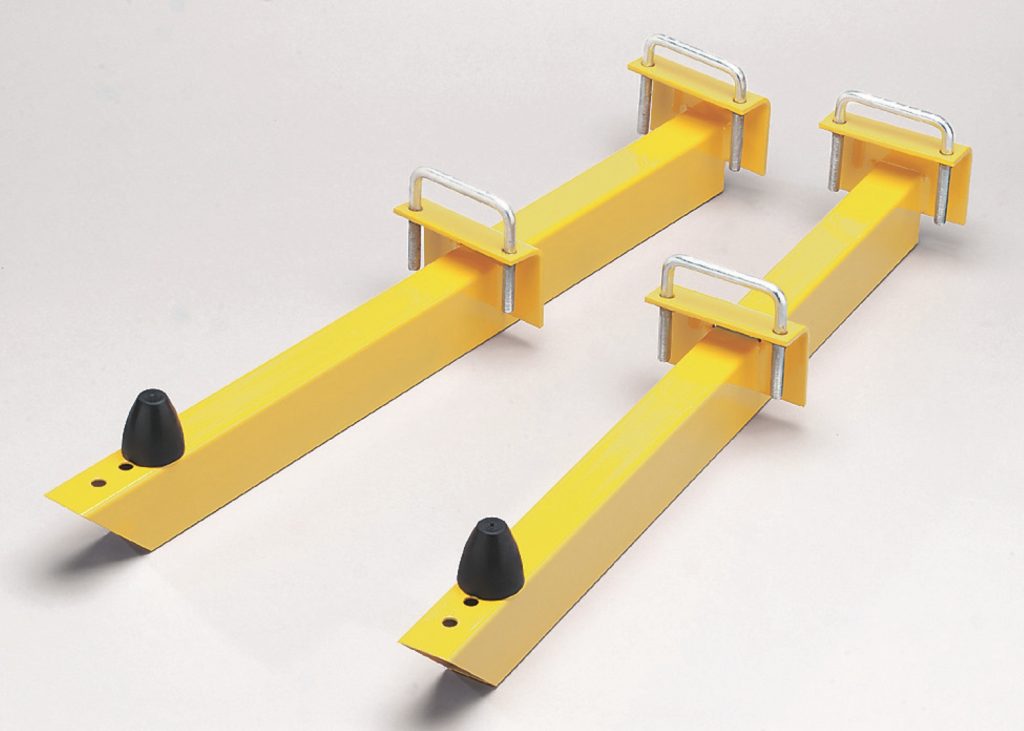

Most people associate the term traction bar with the classic ‘slapper bar’ that bolts underneath a leaf spring. Slapper bars are extremely simple. They use U- or J-bolts to attach to the leaf springs or the axle housing. A snubber at the front of the bar is positioned under the front eyelet of the leaf spring. As the car accelerates and the rear axle pinion angle rotates, the snubber contacts the spring and eliminates wrapup. That helps plant the rear tires for better traction.

Slapper bars for coil-sprung cars replace the lower link. They act much like a slapper bar—as the housing rotates, the front snubber contacts part of the frame or subframe. This in turn picks up the front of the car.

Calvert Racing’s CalTracs Bars are also considered traction bars, but they work differently than slapper bars. They attach to the rear axle and a triangular-shaped bracket mounted to the front leaf spring eyelet. The lower hole in the bracket attaches to the bar, the center hole aligns with the leaf spring eyelet, and the top hole has a pin through it that will ride on top of the leaf spring pack.

As the car accelerates, the axle will wrap and push the link bar forward. A pivot at the front leaf eyelet then forces the pin riding on top of the springs downward into the spring pack. This provides downforce on the entire axle assembly and pushes your tires onto the track surface. The harder you get on the throttle, the harder the downward force on your tires.

Another take on the traction bar are Competition Engineering’s Slide-A-Links. They bolt to the bottom of the spring much like a conventional slapper bar and have a telescopic lower link. As the leaf spring attempts to wrap up with axle rotation, the lower link tube telescopes and torque is transmitted through the sliding link to eliminate bind. Free travel and preload adjustments are made by adjusting the jack screw at the rear of the bar.

In the end, all traction bars are not ladder bars. But ladder bars are traction devices. For more, see the accompanying images.

Awesome article and thank you for sharing