I’ve read engine builds where the builder swears by coated engine bearings and then other guys will say that they are just a way to spend more money and they don’t help at all. I’m building a big block Chevy for my Nova and I’d be willing to spend the extra cash if there is a good reason to use them. What are your thoughts?

P.C.

I have a good friend Lake Speed, Jr. who is a certified oil engineer—called a tribologist.

A number of years ago, I followed along on a rather extensive test that he performed at Shaver Racing Engines in Torrance, California. The test used a 383ci small block Chevy and abused it for several hours using a modification of an SAE test designed to run an engine at very low engine speeds at very high load.

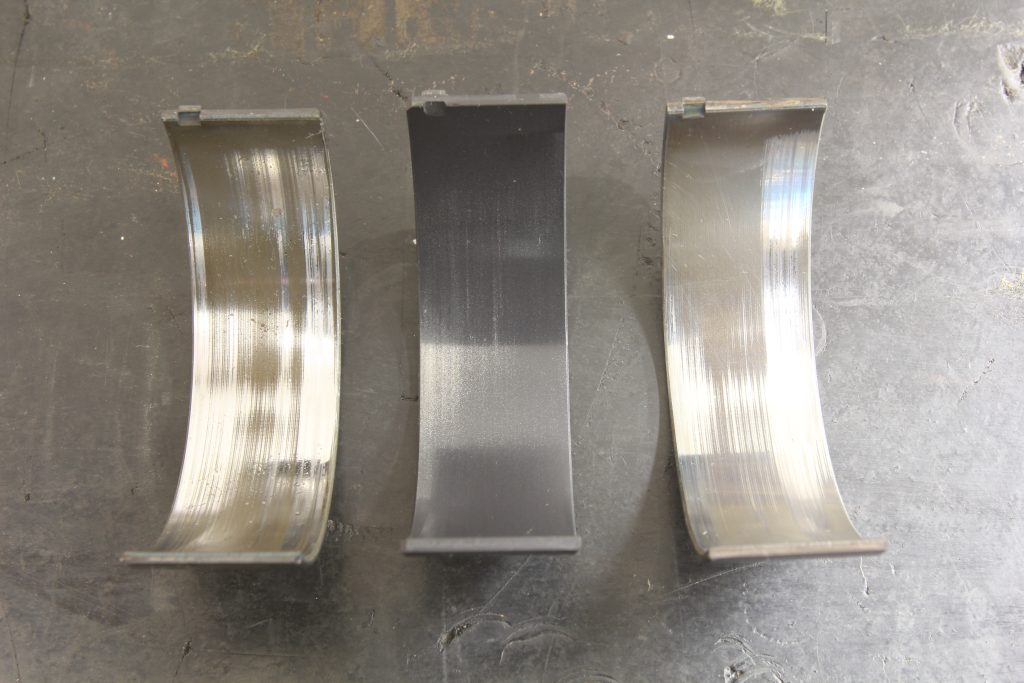

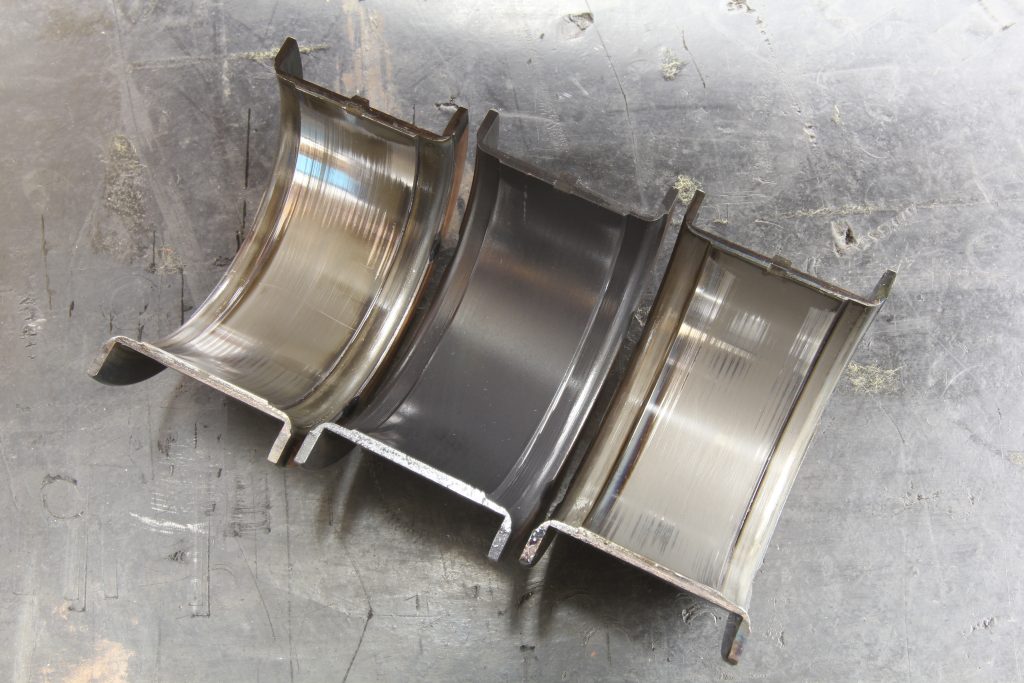

The plan was to run the small block with a set of typical race bearings and then test the used oil for trace amounts of wear metals. The second test would be run exactly the same way with the same oil but with coated engine bearings. Both sets of bearings were from Clevite and the oil was a mineral base 5w20 oil from Driven Racing Oil. They used this lighter oil as a way to further abuse the bearings from near contact between the crankshaft and bearings.

The test subjected the small block to spinning at just under 1,500 rpm at between 175 and 200 lb.-ft. of toque continuously for three hours while performing several WOT dyno pulls up through 6,000 rpm. As we mentioned, this really is engine abuse to run an engine at this load at this low of an rpm. But this will also create the kind of crankshaft contact with the bearings that would be indicative of loads the engine would see over a much longer period of time at higher engine speeds.

Used oil samples were taken at the conclusion of both sets of tests and then delivered to SpeeDiagnostix for analysis. There are several layers of results from each used oil sample test but the most important numbers that this test was looking at were the wear metals present in the oil.

The critical wear metals that SpeeDiagnostix reports offered were the iron, lead, copper, tin, and aluminum counts. The most important ones would be the lead, copper, and tin since these represent the prevalent metals in engine bearings.

The SpeeDianostix test tracks all these materials in parts-per-million (ppm). The wear metal total that includes all of the five metals for the uncoated bearings came to 25 ppm while the total for the coated bearings dropped by more than 50 percent to 12 ppm.

The actual numbers are listed in the accompanying chart, but if we break down the numbers specifically for bearing material to just lead and copper we see these numbers drop even more precipitously. The big one is lead, which plummeted from 11 ppm to 2—that’s an 82 percent drop in wear while copper wear dropped from 5 to 2 ppm or a 40 percent decrease.

So it should be obvious from this test that spending the money on coated engine bearings will clearly result in longer engine bearing life. One aspect that this test did not duplicate is the wear encountered during cold engine start. There is only a very small amount of oil on the bearings when the engine is first started after sitting overnight for example.

Even the best engines require a second or two to generate oil pressure when the engine starts. These few seconds unfortunately can allow a slight amount of wear each time the engine is started. Coated bearings will offer a little more protection against wear during these few moments before oil pressure is created.

This is often why you will see engine builders pressure lube race engines before startup to give those bearings even more chance for a longer life. It’s also why pre-filling the oil filter is a good idea after each oil change—again to create oil pressure a little sooner to help those bearings live a little bit longer.

Engine Bearing Test Results

| Bearing Type | Uncoated | Coated |

|---|---|---|

| Total Wear (ppm) | 25 | 12 |

| Iron | 6 | 7 |

| Lead | 11 | 2 |

| Copper | 5 | 2 |

| Tin | 1 | 0 |

| Aluminum | 2 | 1 |

| Oil Type – Driven 5w20 | ||

Hello, where did the 17% extra iron content come from? Is there greater crankshart wear with coated bearings?

Cheers

That additional 1 part per million in iron is likely a statistical anomaly – it could just as easily been the other way around. I think that when we are talking about 1 part per million difference – that’s really splitting hairs so it’s not something that is really an issue. It’s 1 part in 1,000,000 parts in the oil. The point is that the combinatoin fo coated bearings and synthetic oil are far superior in reducing engine wear. Iron would not be from the crankshaft (the crank in this engine was 4340 steel) – it is more likely coming from the cylinder walls.