Oil analysis.

If you’re an advanced DIYer, you’ve probably heard that term before. The proper nomenclature is actually “spectrographic oil analysis,” and it has been used for decades by oil companies, fleet operators, race engine builders, and others to measure the condition of engine oil.

During this analysis, the user sends a sample of oil to a spectrographic analysis laboratory, such as Blackstone Labs, where a portion of the oil sample is run through a spectrometer. That device analyzes the oil and gives the levels of the various metals and additives which are present in the oil. Those levels are a measure of how much your engine is wearing.

The rest of the sample is used for other testing. An insolubles test measures the amount of abrasive solids present in the oil. The solids are formed by oil oxidation and blow-by. A viscosity test measures the grade, or thickness, of the oil. Whether it’s supposed to be a 5W/30, 15W/40, or some other grade, the lab will know, within a range, what the viscosity should be. Finally, a flash point test measures the temperature at which vapors from the oil ignite. For any specific grade of oil, the flash temperature is known. If the sample flashes at or above that level, the oil is not contaminated. If the oil flashes off lower than it should, then it has probably been contaminated. Fuel is the most common contaminant in oil.

Spectrographic oil analysis, for all its advantages, cannot detect large pieces of debris in the oil. In this case, “large” refers to those particles which are bigger than the microscopic-sized material (smaller than 20 microns) which goes though the oil filter and which spectrographic oil analysis measures. Of these larger particles, there are the “kinda large” ones which are 20-100 microns in size (one micron equals about four one-hundred thousandths of an inch). These get trapped by the filter, but are difficult to see without a microscope. Then there are the really “huge” ones which are over 100 microns and up to .010-inch or so. The oil filter traps these and you can see them easily. Anything larger than that gets stopped by the screen on the oil pump pick-up.

So how do you analyze your oil for debris too small to be stopped by the pump’s oil screen, but large enough to get trapped by the oil filter?

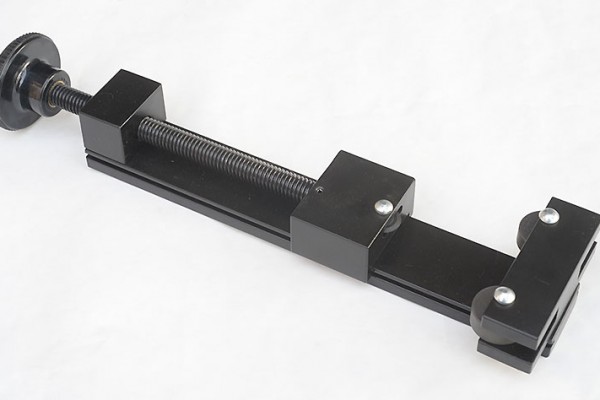

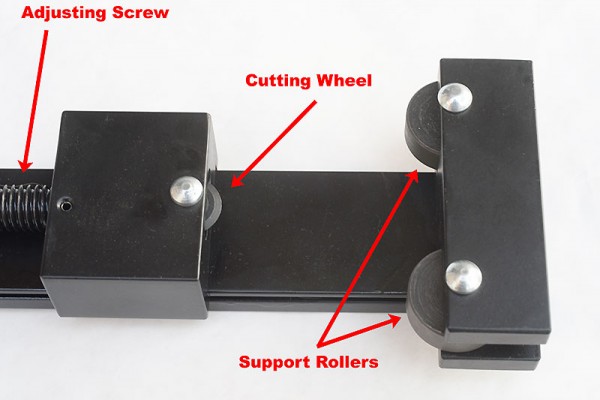

You can use a special tool called an “oil filter cutter” to cut the filter open and visually inspect the filter media. There are a number of these filter cutters on the market, and they vary in price from relatively inexpensive to quite costly. We went looking for a filter cutter of reasonable cost and found one. The Summit Racing oil filter cutter is made of powdercoated, billet aluminum. It works like a giant-sized tubing cutter and is able to cut filters of up to 5 1/2 inches in diameter.

It’s really quite easy to use. After you remove the oil filter, let it drain for several hours. Then, retract the filter cutter by turning the adjustment knob and set the filter on the two bearings so the tool will cut the filter “canister” just below the mounting flange. Next, tighten the cutter against the filter can and rotate the filter. Turn the filter a couple of turns, then modestly tighten the adjuster and turn some more. You’ll follow this turn-then-tighten procedure until the filter can is severed from the mounting flange. Toss the mounting flange and any rubber seals or rings you find at the top the filter in the recycling bin and fish out the element.

Oil flow in a spin-on filter is from the outer circumference of the filter, through the filter media, into the center of the filter, and then upwards and out. Debris trapped by the filter will be visible in the pleats of the media. Use your fingers to spread the folds of filter media apart so you can see down into the pleats. Use a bright light to see into the pleats. What you don’t want to see is metallic debris – metal flakes or dust. When you are done with your inspection, dispose of the filter element in the proper manner for hazardous material.

Now you should have a better idea of the condition of your engine.

Hib Halverson’s article on cutting open an oil filter and spectrographic analysis of the engine oil is right on the money. Since my retirement from the Navy in 1992, spectrographic analysis laboratory usage in the equipment I have come in contact with has been grossly underutilized. Spectrographic analysis is one of the best tools available for machinery. Like a blood test on animals, it gets the facts you cannot see until it is toooo late. When you use a few of these reports you can trend wear and plan accordingly, it works.

Is that why dealers charge $75+ for an oil change?