The Holes Don’t Line Up!

I’m assembling a 427ci big-block Chevy for a friend. It’s an original engine with block and heads that have been in storage for decades that he’s finally putting together. We went to install his factory intake manifold and the bolt holes don’t line up. We can get the bolts in on one side but the opposite side is way off by what looks like one quarter of the diameter of the bolt with the manifold hole raised up away from the bolt holes in the head. Are there different intakes for these older engines? Thanks for your help.

T.L.

It doesn’t help much, but at least we can say—you are not alone. At some point almost everybody runs into a situation like this. What has happened is that at some point in the past these older parts have been subjected to one or more runs through the machine shop milling machine.

Our guess is that the heads have been milled more than once and perhaps the block has also been decked. In the case of the block, sometimes shops will take as much as 0.010-0.015-inch off the block to bring the pistons up closer to zero deck height. This improves compression by tightening the quench but this milling also affects the intake manifold bolt angle.

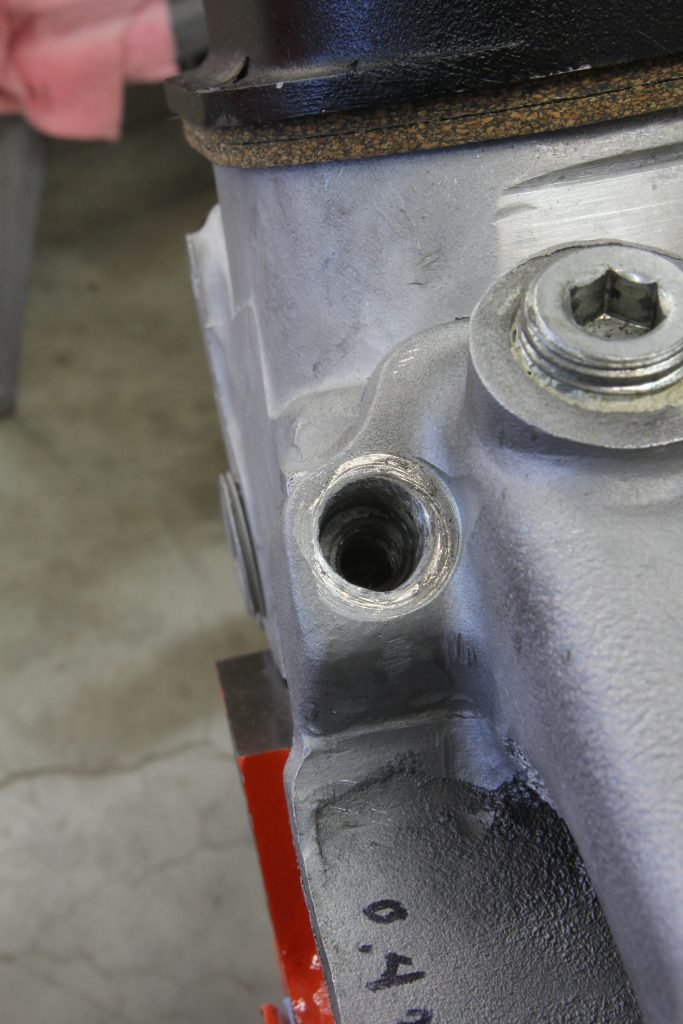

Think of it this way. If you look at the engine from the front, the intake mounting surface of the heads form a “V” angle. If the block and/or the head deck surfaces are milled, this lowers the heads on the engine. This brings the heads in closer to the centerline of the engine. If we lower the heads on this “V” angle, the intake manifold bolt holes in the heads are now lower in relationship to the placement of the intake manifold. The intake manifold sealing surface on the heads is pushed inward toward the center of the “V”. When you position the intake manifold on the heads, the intake manifold bolt holes in the heads are now lower in relation to the intake manifold and there is your mismatch.

Now that we know how this has happened, the repair isn’t all that difficult. The solution is to have your automotive machine shop mill the two angled mounting surfaces enough to allow the intake manifold to fit inside that lower portion of the “V”. Unfortunately, this calls for some Kentucky windage estimation since without knowing how much the block and/or heads were milled it will be difficult to estimate.

We ran into a similar problem on a big-block once where nearly half the intake bolt hole in the head was not showing in the intake manifold bolt opening. We had to guess and had our machine shop mill both intake mounting flanges by 0.040-inch. This is quite a bit of material to remove. In our case, even that wasn’t enough and we had to elongate the intake manifold bolt holes with a hand file in order to allow the bolts to thread into place properly.

We’ve seen some published numbers for small- and big-block Chevys that use a formula of the amount of milling of the deck surface (head or block) times 1.2. Using this formula, assuming the block and/or head has been milled 0.015-inch—this would spec milling the face of the manifold (on both sides) at 0.018-inch. Based on my above experience, it’s doubtful that the engine we worked on had been milled over 0.030-inch so it appears you could go with a 1:1 relationship. This means if the block and/or heads were milled 0.015-inch, then you’d remove the same amount from the intake manifold. Of course, it’s best to test-fit the manifold first. In many cases, the intake does not need to be machined to still fit.

If the manifold mismatch is significant and will require milling at least 0.015-inch off the manifold face, it’s also more than likely that the end sealing surfaces for the front and back of the manifold will also need to be milled. These vertical surfaces have acquired the term “China wall” since on a small- and big-block Chevy these curved surfaces look a little bit like the Great Wall of China.

In our case with the big-block Chevy we had to remove over 0.050-inch from both the front and rear China walls on the manifold in order to create a sufficient gap. This gap is important because otherwise interference will prevent the manifold from sealing on the intake gaskets.

If you are in a bind and have to bolt a manifold on the engine as quickly as possible and there’s no time to have a machine shop mill the manifold, you can try elongating the holes in the intake manifold. In our case, the mismatch was so severe that we first tried elongating the holes but ended up having to mill the manifold in addition to the elongating the holes, but this was probably a result of an engine with significant milling to both the engine block deck surface and the block deck surface.

Generally if the block and/or heads have not been milled more than 0.010 to 0.015-inch, the intake should fit with no problem. Don’t be too concerned if there is some mismatch between the intake manifold port and the cylinder head. While much has been written about making sure this mismatch is idealized, it’s really more of a make-work exercise. We’ve seen a 1/8-inch step between the intake port and the intake manifold (where the intake manifold opening is larger) that does not affect power on a typical street or mild performance engine.

We’re not talking about a Pro Stock engine here but rather a typical street engine. The mixture velocity that fills the cylinder is concentrated in the center of the port while at the port walls the velocity is near zero and has little impact on airflow. So all that stuff you may have seen on the internet about how to port-match intake manifolds is for the most part a waste of time. We expect we’ll hear from the internet engine experts on this statement, but again, we’re talking about a mild street engine. If you are building a full-bore competition engine then yes, it’s a good idea to port match the manifold. But for a normal street engine, there are many more important areas where you should concentrate your energies.

Sealing the intake manifold to the head is far more important and it’s worth noting that once the bolt holes all line up, that does not mean the intake is properly sealed. We’ve written a column that addresses this issue (find it here). The problem is often that the bottom of the intake manifold opening angles away from the intake port in the head which does not adequately load the intake gasket. This incorrect load on the gasket allows the intake manifold vacuum to pull oil out of the lifter valley and into the intake port. This can consume a sizable amount of oil in a very short time and yet the problem is hidden by the intake manifold so the oil usage is difficult to diagnose.

So as you can see, there are several issues that can create problems in an otherwise seemingly simple interface between the intake manifold and the cylinder head. Our advice is to tread carefully and pay attention to the details. It will save you time and aggravation later.

[…] The Holes Don’t Line Up! I’m assembling a 427ci big-block Chevy for a friend. It’s an original engine with block and heads that have been in storage for decades that […] Read full article at http://www.onallcylinders.com […]

If you wanna pick fly shit out of pepper while wearing boxing gloves, go ahead. But slightly mismatched ports. wouldn’t make any noticeable difference on most of the dynamometers in use today. Correct the concern and try to see the difference A couple degrees in air temperature would be more noticeable. I have done testing on very expensive electric dynamometers and it takes a severe misalignment to make a significant difference.

Hey Jeff, I have a bit of a conundrum. I’m putting a 427 l89 together. I picked up a set of aluminum 842 heads that look like they’ve been milled to hell and cost a fortune. The block and tri power are untoched.

I’m going to have to do an old time broching on the block to remove the numbers at sometime.

I haven’t thrown anything together yet. What is the best way to measure what the space is at the gasket face on the head that will allow it to sit as it came from the factory.

I’m not too much into cutting the intake as it’s rather pricy.

Dam they used to pile up leaky shims to fix this lol.

Please let me know if you can help. I can send a few pics of the heads so you can see how much material was removed.

Heres a quick idea. Head one… I would say the angled head of the vale is about .010 proud of the deck at highest valve. Head 2…. I would say that number is closer to .020. You can also tell when they are laid upside down with that little patch of sand cast thats on the exhaust sides. It’s gone on head 2 and a about .010 remains on head one.

Hope you can lend a hand.

My email is in the fill lines if you can e mail me, so I could show you pics

Does any of this milling effect the distributor and it’s hieght? and is there a formula for that??

My thoughts are that if you just file the holes to allow for the bolts to line up, you have not addressed the alignment of the intake and the head and wouldn’t this cause a eddy in the air flow?

I just had tacos for breakfast

I have a 1972 454 Corvette with oval port heads. The engine has been bored to 460 It’s equipped with a Hydraulic roller cam and topped off with a Torker 2 intake and TB EFI. Can I run an LS-6 manifold with rectangular ports?